‘Family ties are long lasting and the relationships between parents and children are likely to continue far beyond any periods of living apart’ (Family Rights Group 1994 cited DHSS, 2020).

Reunification, like other aspects of permanency, requires unwavering, committed case work. There is great responsibility to get this challenging area of service delivery right. Practitioners need to navigate multiple tasks and needs within clear timeframes to support families to have the best possible chance of coming together again after a period of separation. It also requires the careful balance of ensuring alternative plans are in place that will provide long-term stability for the child just in case they are not able to return home. The importance of this work starting with families from day 1 of when a child is brought into care cannot be underestimated. Starting early enables practical, realistic actions to be established which form the foundation for ongoing work with a child and family.

Tip

Think about crisis intervention theory and how it can help to orient those initial contacts with the family towards identifying clear actions with concrete, achievable tasks that parents can start working on straight away.

Effective practice towards reunification requires holistic decision making to ensure the focus of interventions is not lost amongst organisational and systemic pressures and frustrations. These frustrations can sometimes impact on objectivity and practitioners may find it easier to notice evidence that supports, rather than challenges, negative perceptions of a family, particularly if they are tricky to work with (NCCD, 2018). Also, once the immediate risk has been addressed by bringing the child into care, it can be tempting to put the work aside to focus on more pressing priorities with other children and families. Find ways to maintain the urgency and rigour required to progress structured, safe and timely reunification and be proactive in seeking positive outcomes for a child. Breaking that momentum can contribute to a child drifting in care.

Talking about reunification

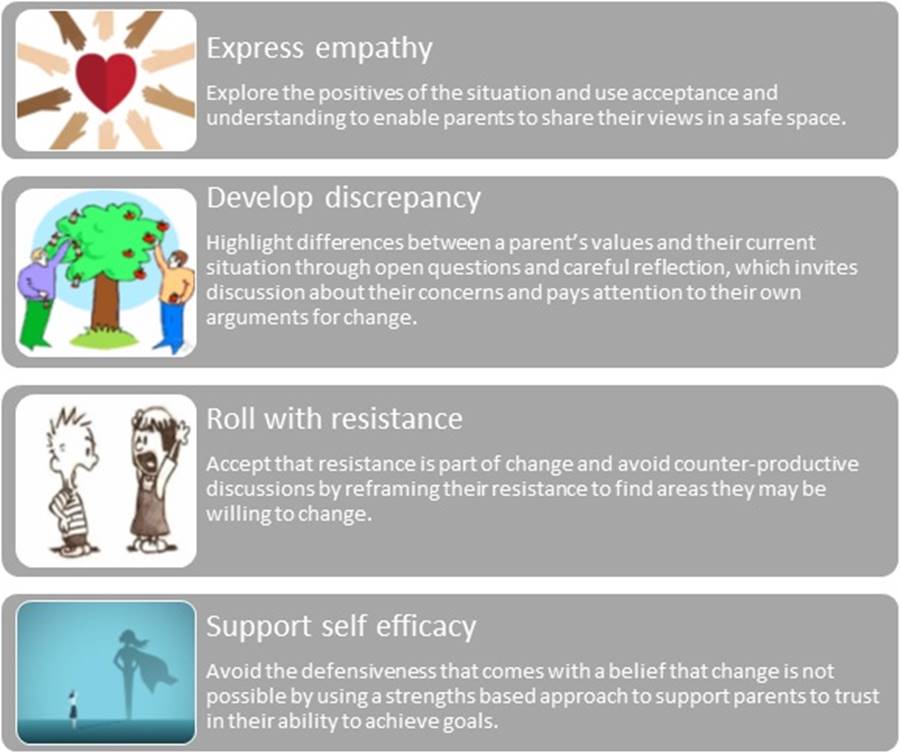

The decision to reunify and the process of reunification is made up of numerous conversations with the child, family and their network. Conversations with parents are central to this and require practitioners to draw on communication skills based on unconditional positive regard to work with the resistance, anger, disempowerment, shame and grief a parent experiences when a child is removed from their care.

From day 1, parents need to understand the reasons a child entered care (immediate harm indicators recorded in the safety assessment), the ongoing risks to the safety of the child, and how to achieve safety and demonstrate acts of protection. Using the Collaborative Assessment and Planning Framework tool with parents helps to build a picture of these elements and to ensure both strengths and worries are considered. This informs the development of the case plan and the Safe Contact Tool. Transparent conversations will help to clarify what they can expect from practitioners and what practitioners will expect from them. Explain the non-negotiables and then work together to develop solutions.

It is important to communicate clearly that reunification is the preferred primary permanency goal. The process of achieving this outcome also includes conversations around concurrent case planning and the need to involve the family in planning for an alternative permanency option just in case reunification cannot occur. Consider the Framework for Practice values of family and community connection, partnership, strengths and solutions, curiosity and learning. Ensure conversations with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families are shaped by the elements of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Child Placement Principle, especially partnership, participation and connection. Involving an independent person and the Family Participation Program can strengthen participation for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander parents and older children.

Practice prompt

In amongst the many conversations and tasks which need attention early in the intervention, there are four key activities to start working on with parents after their child has been removed which can support active reunification:

- Ensure a genogram and kinship mapping is completed and up to date. As well as being essential tools when case planning to strengthen permanency, the process of putting them together can help to build relationships.

- Engage with and build the safety and support network. This helps to show parents from the outset that the network matters.

- Make decisions about contact and establish family connection time. Review arrangements regularly and make adjustments if required.

- Plan for a Family Group Meeting to develop a case plan and get the Family Led Decision Making process underway with a referral to the Family Participation Program or the Collaborative Family Decision Making team.

Change is not easy

Progress towards reunification will be supported by partnering with parents to build a network and find motivation to make the changes necessary to enable their child to return to their care. Acknowledge that these changes are hard and at times can feel overwhelming. Use a strength based approach to consider parenting capacity alongside how they may function day-to-day – some days are better than others, and a parent’s capacity may be greater than what their functioning may appear on a bad day.

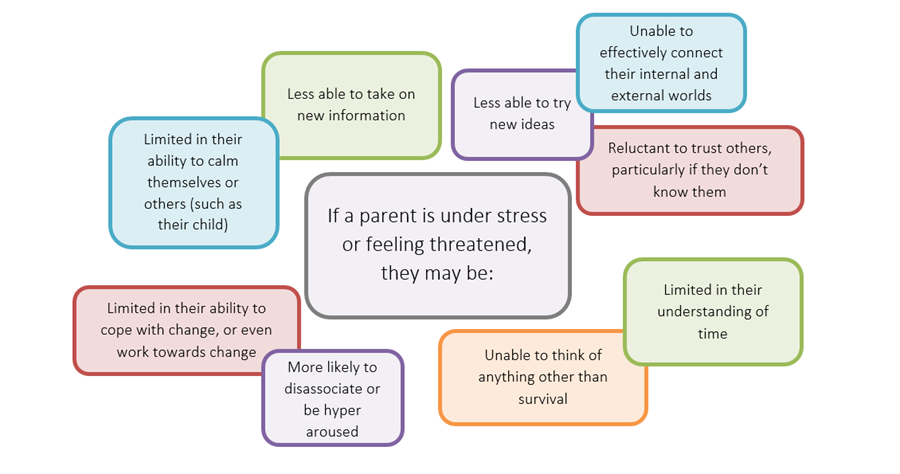

Parental function under stress or threat

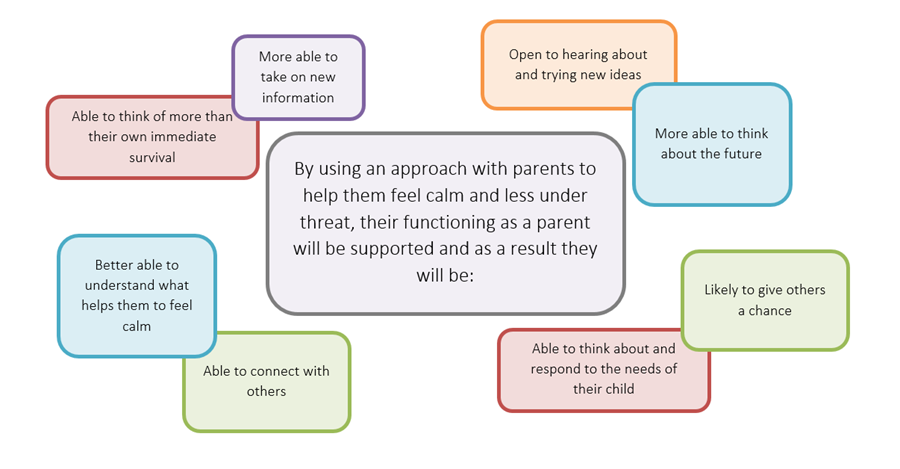

Support a calm environment to promote change

Privilege and oppression

Maintaining a position of curiosity and learning can help to understand the behaviour of others. How can the lens of privilege and oppression help to put things into context when working with a family towards reunification? Be mindful of the privilege practitioners hold when working for a statutory authority as well as other characteristics that lend themselves to positions of power.

Attention

Some Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families may be resistant to engage in working towards reunification. Consider and explore whether this is because they have the belief, based on history and systematic oppression, that once a child is removed, they will never be returned. Contact may be too painful and it is easier to let go than have hope (NCCD 2018).

Some strategies to build connections and navigate the differences created by privilege and oppression include to:

- differentiate between who a person actually is and their behaviour

- recognise the power imbalance

- check in about a behaviour or response to avoid a misunderstanding

- acknowledge if something is unclear

- remember RUAD

- Recognise and name what is different to be able to work with it

- Understand the difference by asking questions and learning about it

- Appreciate and value what difference can bring to a situation

- Difference can be used to improve practice and outcomes.

The importance of hope and motivation to change

Further reading

Resistance is futile? Exploring the potential of motivational interviewing. This article explores using motivational interviewing in the context of substance abuse.

Remember to emphasise the role of the network and how essential this is to support hope and motivation to change. Involvement with Child Safety can make parents feel isolated for many reasons, including if they are embarrassed or ashamed about their circumstances. Ask them to think about people that care for them and their child, who can help and support them through this journey. Through the reunification process, consider how the network can grow and help keep parents motivated. Without motivation, practitioners may see compliance but not real, lasting change (NCCD, 2018).

Practice prompt

Use the Circles of Safety and Support Tool to continue to help identify who is part of the network.

Further reading

Refer to the practice kits Alcohol and other drugs, Mental health, Child sexual abuse, Domestic and family violence (Working with mothers experiencing violence and Working with fathers) and Disability for more information around working with parents.

Published on:

Last reviewed:

-

Date:

Content updated for SDM changes.

-

Date:

Maintenance

-

Date:

Maintenance

-

Date:

Page created