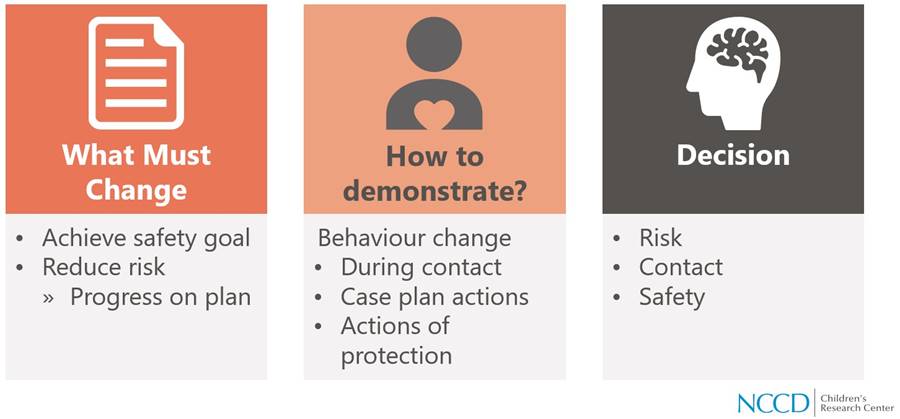

As discussed, honest and transparent conversations will help to build strong relationships with a child and family to partner with them around key decisions about reunification and alternative plans for permanency. When working towards reunifying a child to the care of their parents, there are three things that need to be clear from day 1 – what needs to change, how this change can be demonstrated and the need for a clear decision based on risk, contact and safety.

(NCCD, 2018)

What must change

Collaborative case planning for reunification includes a focus on both strengths and needs and can be articulated using worry and goal statements.

Use worry and goal statements

How to demonstrate change

Contact or family connection time is an important opportunity for parents to demonstrate changes in behaviours which will enable them to safely care for their children. Keeping the importance of ‘reunification from day 1’ in mind, practitioners need to arrange contact between the child and their parents as soon as possible after the child has come into care. In the midst of the demands that come with this phase of intervention, think about where contact is facilitated. Use the service centre setting only if the risk is extremely high and cannot be moderated in any other way (NCCD, 2018).

How practitioners talk about contact can influence the way a family makes sense of the situation and expectations. Instead of using the term ‘contact’ in your discussions with a parent, try talking about ‘family or connection time’ with their child to see if this helps to provide context (NCCD, 2018). Also, rather than using the term ‘supervised contact’, discuss with the parent how Child Safety being present can support a child to be safe as well as offer coaching and guidance.

Attention

What might surface for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families when the term ‘supervision’ is used?

Planned, purposeful connections

To support a family to draw the most out of family connection time (contact) and move towards reunification, think about developing a proposal which reflects the worries, goals and actions identified in the case plan. Consider the key elements listed below in terms of the child’s needs, enabling the skill development of parents and how this time together can be used to make decisions about stability and reunification:

(Adapted from Rose Wentz (wentztraining.com) by CQ region)

Take every opportunity to reinforce with parents the importance of spending time with their child. Let them know their child needs to see them being proactive in their efforts to change their behaviour and trust that this will help to bring the family back together again. Family time is a good opportunity for parents to practice and demonstrate knowledge and skills that work towards achieving their safety goals. Support parents to set realistic expectations and acknowledge that there will be mistakes along the way. Put mistakes in the context of learning and take the opportunity to positively influence their parenting behaviour. Consider that a therapeutic focus to this time can support connections, nurture attachment and maintain relationships (Farmer, 2018; Wilkins and Farmer, 2015).

Practice prompt

Help parents to think about how setting up hello and goodbye rituals and planned activities during family contact can support relationship building, behaviour change and create easier transitions for their child (Wilkins and Farmer, 2015).

The voice of the child

Children can provide great insight into how family time is going. These views can inform the case plan and decisions around what actions are required to keep progressing towards reunification. The Three Houses Tool and The Safety House Tool are familiar tools for most practitioners and can be helpful in drawing out the child’s voice and keeping this central to the process. Use The Three Houses Tool to explore behaviours that frighten and worry the child and to explore protective factors that can shape case planning for safety. It can also help to create a picture of what needs to change for the child to feel safe and happy. Use The Safety House Tool to hear from the child about who and what can keep them safe, what rules need to be in place and how the family can get to a point where the child actually feels safe.

While it is important to be as flexible as possible when arranging family time, taking into account the child’s wishes and the stage of the reunification process (Wilkins and Farmer, 2015), the logistical challenges of trying to organise contact can be extremely frustrating. These frustrations can at times overshadow the importance of this time and cause practitioners to lose sight of its purpose (NCCD, 2018). Try to reframe the frustrations and remember the benefits to a child and their parents of spending time together. It can:

- reassure the child

- maintain and nurture the relationship between a child and their parents

- enable parents to practice and demonstrate new skills in a safe setting

- provide practitioners with an opportunity to observe the relationship between a child and their parents

- allow practitioners to assess how a parent approaches parenting tasks (NCCD, 2018).

The importance of the network to support contact

The family and network need to work together to support parents to make progress on the plan that will result in visible changes to reduce the risk to the child. Document this in the case plan using words and language that make sense to everyone involved.

The importance of networks in ensuring case planning maintains connection to family, community and culture cannot be underestimated. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families have been using a form of safety and support networks in the raising of children for generations. Be aware that the care of a child is not limited to the immediate family; rather there is a collective community focus. With ‘one community, many eyes’, someone is always watching out for the child, knows who they are, their name and the family group the child belongs to. At the heart of the collectivist approach to child rearing is the emphasis on protecting a child and preserving their wellbeing.

Extended family members and other community members, such as local Elders, are particularly valued for the ongoing support they offer parents and children. The extended family network also provides lifelong learning opportunities for all family members. A community of kin can help parents with a sense of security, trust and confidence in the knowledge that others are always there to help them care for their children.

Ensure the network for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families includes relevant support agencies such as the Family Wellbeing Service and Family Participation Program, who assist with keeping statutory child protection processes culturally safe and understand what is needed to enable families to identify the best way to ensure quality care for their children (SNAICC, 2019).

Make the most of family time

Best practice principles guiding contact or family time include:

- the provision of opportunities to address connection and belonging

- a gradual increase in the frequency and duration of time together as parents demonstrate progress

- the development of an agreed family contact schedule within the case plan

- preparation for contact and reflection afterwards about what worked well and if there are any worries

- emphasis on the role of Child Safety at contact to support a child to be safe and actively help a parent to respond appropriately to their child during connection time (reframe inspectorial role)

- clarity and transparency around any non-negotiable contact provisions to keep the child safe

- discussion with the child if contact arrangements are different to what they would like (NCCD, 2018)

- plans to support contact with others who are important to the child, such as siblings and extended family - how can they be included in contact while still allowing the care and actions of the parents to be considered? Do parents rely on others to do things for the child? Do they remain actively engaged or do they sit back?

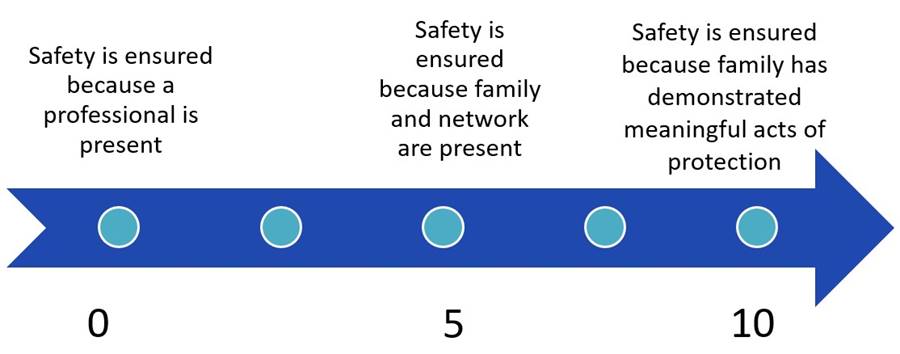

Family time seeks to balance three key needs – for a child to be safe, for family connections to be maintained and for parents to have the opportunity to safely practice and demonstrate protection and appropriate responses to risk. To gain the most out of connection time, try using this scale to help parents see where things are now, where they need to be and how the safety and support network can provide support and build safety:

Remember that parents can demonstrate behaviour change and acts of protection when their child is not in their care. Engagement with support services, attendance at courses, securing stable housing, establishing and growing networks and choosing to spend time with those who care for them rather than those who encourage their involvement in harmful behaviours are all tangible ways a parent can show they are working towards a real change in behaviour.

Attention

Attending services does not mean that safety is increased or achieved. Pay attention to all behaviours that relate to the case plan goals and impact positively on the child (NCCD, 2018).

Plan to increase parent and family involvement

When the primary goal is reunification, case work will have a strong focus on maximising the parents’ activities in meeting the child’s safety and care needs. When the alternative goal is long-term care, case work will still have a strong focus on maximising the parents’ activities however the carer and network will have the main role of meeting the child’s care needs.

When developing case planning goals (both primary and alternative) and actions, it can be useful to think about the child’s care needs across different domains, such as health, education, social/recreational and cultural. This helps to explore and define who is currently involved, what are they doing now and what could they (safely) do in the future.

Tip

When thinking about activities a parent can be involved in, think about why they wouldn’t be involved. If there is no safety risk, find ways to bring parents on board.

Some areas that parents can be involved in are listed below. Safety risks to the child determine a CSOs involvement.

| Health | Education | Social/Recreation | Cultural |

|---|---|---|---|

| Caring for the child’s health can include: | Supporting a child’s education can include: | Supporting a child’s social development and recreation can include: | Supporting the child’s cultural connection and identity can include: |

|

Organising and attending routine appointments and check-ups with the GP, child health nurse, dentist, optometrist. Deciding about medication and treatment and support the child to have their medication and treatments. Attending appointments with specialists and allied health services. Getting the child treatment and medical care in an emergency. Receiving information and advice about the child’s health and development. Advocating for the child. |

Getting them to and from school safely, including getting lunches ready, bags packed and dressed and ready to go. Talking with the teacher about the child’s progress. Helping them with homework and assignments. Attending parent teacher interviews and meetings. Attending special school activities and events such as assembly/parade, awards, performances. Contributing to the child’s Education Support Plan (ESP). Working with the school about problems including discipline and behaviour. Completing permission slips. Helping at school events. |

Being involved with extra-curricular activities, clubs and groups. Watching swimming lessons. Taking the child to birthday parties and social events with friends. Attending community events and functions with their child. Learning a new skill together (such as music lessons). Enjoying an existing hobby or past time together. |

Reading, talking about and seeing things to do with their culture. Finding out about their family tree and the lands and community where they are from. Taking their child to culturally significant events, activities and traditions. Together they spend time with people from their culture. Meeting and connecting with elders. Collecting artefacts and personal items that hold cultural value. Participating in cultural activities such as dancing, painting. |

Practice prompt

Think about …..

What the parent is doing now in relation to this aspect of the child’s care

What the carer is doing

What Child Safety is doing

What the parent could start doing that would increase their involvement, even slightly

What the barriers are, and any complicating factors and harm/worries

What is safe and practical.

Use the Safe Contact Tool to record the activities a parent can be involved in where there are safety concerns. This also provides the network with information about what different people can do to make sure the child is safe and work towards increasing the parents’ involvement.

Further reading

Practice guide Family Contact for children in care

Refer to the Safe Contact Tool to identify safety risks and demonstrated behavioural changes to support an increase in family time when working towards reunification.

Decisions

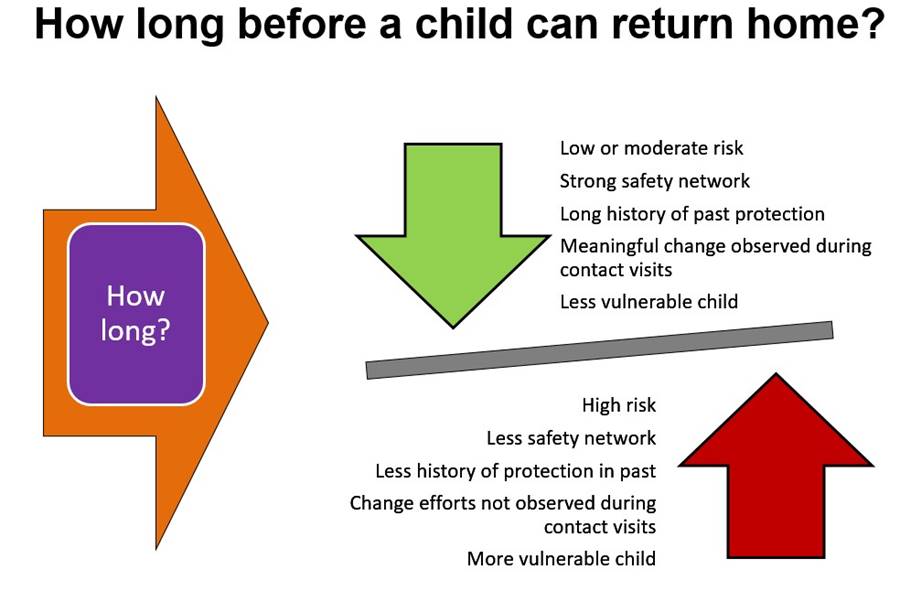

Decisions aren’t made at one point in time of a child protection intervention. Multiple decisions are made every day at every phase and are more often than not influenced by many factors and complexities. When working towards reunification, practitioners can often struggle with knowing how long it can be before it is safe for a child to return home. The following graphic outlines some of the elements of risk and safety that must be balanced to inform decision making. Is there anything else that needs consideration?

When working towards reunification, consider the following questions:

- Can the child be returned home safely?

- Is reunification still viable?

- Is there an alternative permanency option if reunification is not possible?

When considering these questions, think about risk to the child, the safety of the child, and how family contact has been over the time the child is in care.

Share with parents how these factors contribute to increasing (or decreasing) the chances of reunification. For example, when thinking about contact, if a parent consistently attends and is responsive and positively engaged with their child, the likelihood of reunification is increased. Not showing up or causing harm to the child during connection time will clearly decrease the possibility of reunification.

Decision making about reunification is difficult

A robust long-term safety and support plan will also guide decisions around reunification. It is important that all stakeholders involved are on the same page regarding reunification and where things are at. If there are different narratives – for example, a parent is ready for the child to return home but the child is not – there is potential for reunification efforts to be unsuccessful.

Practitioners often work with families over an extended period of time and in doing so, gather a wealth of information. It can be hard to sift through these details to decide when it is the right time to stop progressing reunification. Some other factors that contribute to difficulties in decision making include:

- contradictory information

- doubts about whether practitioners have a true understanding of what a parent is like

- emotional responses when things aren’t going well

- systemic pressures, such as timeframes

- differing stakeholder views

- if there is enough evidence to support decision making in court

- the gravity of making the decision to progress reunification or not.(NCCD, 2018)

Note

Remember you are not making decisions alone:

- Look at the evidence of change when reviewing the case plan, to guide the decision of when to stop progressing the primary permanency goal of reunification and shift focus to the alternative goal identified and developed through concurrent case planning.

- Use supervision or a case consultation to help you make your assessment

- Convene a practice panel with a critical friend (and more than one Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander person for Indigenous children) to inform decision making.

- Hold a family group meeting involving the parents and key network members to ensure the network can contribute. (Refer to the Family Participation Program for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families.)

-

Resource

Collaborative assessment and planning framework - worry statements

Read more -

Resource

Collaborative assessment and planning framework - goal statements

Read more -

Resource

Family contact for children in care

Read more -

Resource

Safe Contact Tool

Read more This is a secure resource. Only authenticated users may access this content.

Working with families towards reunification

NextWhat happens if reunification is not possible?

Published on:

Last reviewed:

-

Date:

Maintenance

-

Date:

Content updated for SDM changes

-

Date:

Maintenance

-

Date:

Maintenance

-

Date:

Page created