As noted earlier, young people who are transitioning to adulthood have the same needs as those who are not in care, but they also face a range of unique issues and circumstances that highlight their need for particular support during this time.

Contemporary research indicates that young people leaving care have a significantly greater risk of becoming involved in homelessness, unemployment, juvenile crime, problematic substance misuse, poverty, prostitution, young parenthood, social isolation and mental illness. The transition into adulthood is a critical developmental event in the life of a young person, and it often presents them with a range of specific challenges and opportunities.

One key difference between young people who have left care and other young adults is that most young people who reside with their parents live at home until their early twenties. Their movement towards independence usually involves a long transitional period during which they may leave and return home multiple times.

This safety net of a secure and supportive family and related support network is not always available to young people who have been in care, particularly when they have experienced numerous care environments or continue to have a disrupted relationships with family.

Additional consideration must also be given to young people transitioning to adulthood who may experience barriers to participating fully in opportunities, including those who:

- are Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander

- are lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer or intersex

- have disabilities

- have been a victim of crime

- live in rural or remote areas

- are from a culturally and linguistically diverse background

- are pregnant or are young parents

- are homeless or highly mobile or have had multiple/unstable care arrangements

- have contact with the youth justice system

- have mental health conditions

- engage in problematic substance misuse issues

- self-harm.

Working with a young person with a disability

The following approaches can be helpful to ensure young people with a disability experience a planned transition to adulthood:

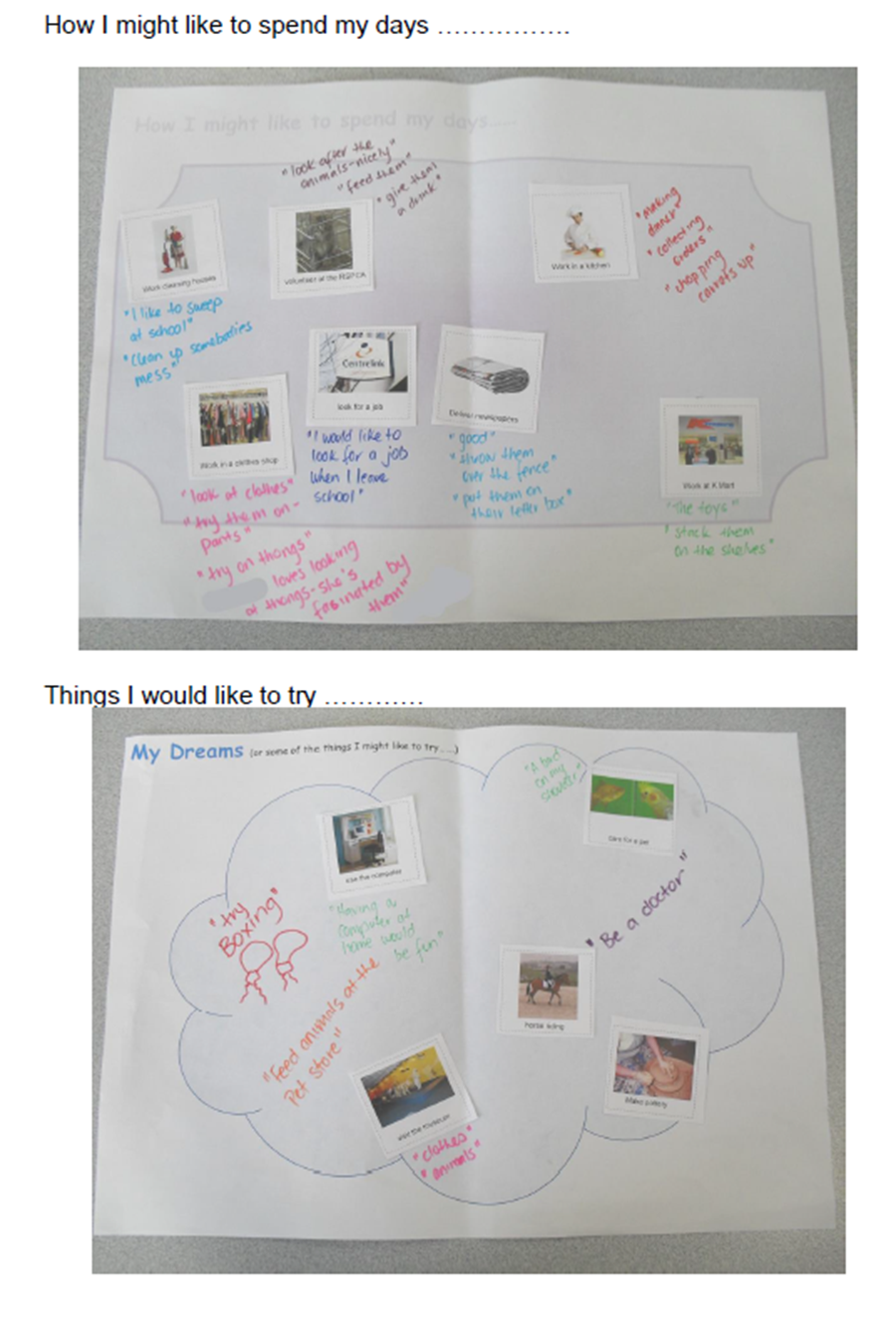

- Ensure the young person has a genuine opportunity to participate in the planning process by using a person-centered planning approach to discover how they want to live their life, and what is required to make that possible.

- Adapt the plan so that it is accessible and meaningful to the young person. This may include the use of photos or a visual representation of the plan.

A person-centered planning process using visual methods could look like this:

- Use the young person’s existing National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) participant plan and professionals identified in the plan to inform the planning process. For example, a speech and language therapist who works with the child can assist in eliciting their views.

Young people who are already receiving supports through the NDIS may benefit from a more comprehensive assessment in partnership with the child’s guardian or representative and the NDIS support co-ordinator, to assist with NDIS plan reviews when they are 17. This will ensure the young person has an NDIS plan that will meet their needs, particularly in terms of funding for the supports needed in independent living.

Young people with complex disabilities (especially those with child related costs and placement and support (CRC-PaS) arrangements) who require very high levels of daily living support, may need significant planning for funded adult care arrangements. Planning for this will need to start well ahead of the young person reaching adulthood to ensure assessment of needs, approvals of funding, and transition to new care arrangements.

NDIS accommodation and support arrangements for young people transitioning to adulthood may include:

- supported independent living and independent living options

- specialist disability accommodation options

- school leaver employment supports for young people who need extra help to achieve their employment goals.

Time sensitive

Don’t just allow adequate time for the planning and all the other administrative tasks that are needed for transition, but also allow time for the young person to understand the process, think about what it means for them and to generate their own questions about it.

Transition and post care support teams

The Transition and Post Care Support Program is provided by the Specialist Services Team and was established in response to the needs of those young people with disability, mental health needs, and/or complex and high risk behavioural, psychological and/or emotional needs who are at most risk of homelessness as they transition to adulthood.

Transition officers provide direct support to young people in care to ensure they experience a safe and stable care arrangement that supports community living, involvement in work, training or appropriate daytime activities, and helps build and maintain relationships.

There are 12 transition officers across the state, with at least two in each region. A transition officer can start supporting a young person in care from 15 years of age, with support increasing in intensity at the ages of 16–17 years and through transition. Post care services are available for young people up to 21 years of age.

Services are prioritised for those young people who are most at risk of homelessness as they transition to adulthood or who are experiencing homelessness after care.

How can the transition and post care support team help?

Transition officers use an approach that involves important stakeholders at all stages of service delivery, including the development, implementation, monitoring and evaluation of transition from adulthood plans.

Transition officers provide direct support to young people to build skills that improve their likelihood of successfully maintaining tenancies and co-tenancies—reducing the risk of homelessness.

How to request support?

Initial contact can be made directly with the transition officer in your region. The transition officer may provide further information about the program, its services and the target group.

Where ongoing support and suitability for the program is identified, local processes for formally requesting support from Specialist Services should be followed. This may include completing a Request for support form. Any request will include written confirmation that both the regional line manager and the senior program officer are aware of the need for support.

When a young person has impaired decision-making capacity

The Queensland Civil and Administrative Tribunal (QCAT) can make decisions about decision making for adults with impaired capacity, including financial decisions (administration) and personal and health decisions (guardianship).

When a young person with impaired decision-making capacity requires their interests to be protected and their needs to be met after they turn 18 years of age, we need to make an application to QCAT as soon as possible after the young person turns seventeen and a half years. This allows adequate time for the investigation and hearing by the tribunal. The transition officer will know a lot about substitute decision making and the role of QCAT and the Office of the Public Guardian and will be able to provide advice and support to the CSO.

According to QCAT, there are three elements to an adult making a decision:

- understanding the nature and effect of the decision

- freely and voluntarily making a decision

- communicating the decision in some way.

If an adult needs to make a decision and is unable to carry out any part of this process, they have impaired decision-making capacity.

QCAT can decide a range of matters about adults including:

- making a declaration about an adult’s decision-making capacity for some or all matters

- determining if informal arrangements in place are adequate to protect the adult

- appointing a guardian to make some or all personal and health care decisions

- appointing an administrator to make some or all financial decisions

- making a temporary decision to deal with an urgent situation

- making a declaration about the execution and appointment of an enduring power of attorney.

See Decision making for adults for more information about the role of QCAT and how to make an application.

The Office of the Public Guardian is very clear that if someone has impaired decision-making capacity it does not mean that they can’t make any decisions. The law states that people with impaired decision-making capacity have a right to adequate and appropriate support in decision making. The OPG uses a structured decision-making framework to ensure a young person with impaired decision-making capacity can meaningfully contribute to decisions made about them.

See Guardianship and decision making for the full framework and further information about guardianship.

Working with a young person and their sexual and gender diversity

Practice prompt

We need to be mindful of our language

The term ‘sexual and gender diversity’ is replacing the acronym ‘LGBTIQ’ and responds to criticism that, while LGBTIQ refers to a community of people who share some things in common, there is also diversity within these categories.

Use of this term is encouraged, and over time it may start to replace the existing acronym which is still current in research cited below.

The LGBT(I) population tends to be lumped together as if it were one homogeneous group of people, and nothing could be farther from the truth. Lesbian youth have different issues than gay or bisexual young people, and more specific investigation is needed in these areas. Just as one program does not meet the needs of all youth in foster care, individual distinctions must be addressed within the LGBT(I) population as well.

(Banghart. 2013, p. 153)

There hasn’t been a significant amount of research into the specific needs of young people in relation to sexual and gender diversity. However, Banghart (2013, p. 3) notes that what is known about the experiences of sexually and gender diverse youth while in foster care is not encouraging. Several older studies report a tendency on the part of the child welfare system to either ignore the sexual orientation, gender identity, and gender expression of these youths to actively discriminate against them because of it (Mallon, 1998; Jacobs & Freundlich, 2006; Wornoff & Mallon, 2006 cited in Banghart, 2013, p. 3).

Craig-Oldsen, Craig and Morton (2006) also report that meeting the developmental and emotional needs of youth in foster care can be even more challenging when these young people are attempting to understand their sexual orientation and gender identity in a non-supportive environment (cited in Banghart, 2013 p. 4). For example, this may be due to the limited capacity of foster carers, who may not have adequate knowledge and training about sexuality issues, or because religious and social beliefs hinder competent care.

Due to the stigma and discrimination that sexual and gender diversity can provoke, some young people may be in various stages of being open about their sexual orientation and gender identity to the broader world. Therefore, it can be more difficult to engage the young person in discussion about the issue and the impact this may have on their transition to adulthood. Provide young people with the opportunity to discuss this if they feel comfortable to do so.

Tip

Help for young people exploring their sense of sexual and gender diversity is available from:

Open Doors Youth Service. Telephone 3257 7660 (counselling for sexually diverse young people aged 12 - 24).

The following resources from CREATE aim to assist in working with children and young people in care who identify as sexually or gender diverse.

LGBTQ Do's and Dont's

Further reading

Berberet, H.M. (2006). ‘Putting the pieces together for queer youth: A model of integrated assessment of need and program planning’, Child Welfare, 85(2), 361–384.

Working with a young person with mental health difficulties

The transition process may cause young people to feel anxious. This understandable tendency is heightened for young people experiencing mental health difficulties. Instability in care arrangements, disrupted attachment to caregivers and sexual abuse in care may adversely affect a young person’s mental health when they leave care. The transition period may act as a trigger for mental health difficulties, self-harm or suicide.

We can improve outcomes for young people with mental health problems and/or problematic drug and alcohol use when they are transitioning to adulthood by:

- ensuring there is collaboration between agencies working on mental health services and child safety

- following an outreach model of support service provision with a shared focus on the complete needs of a young person.

Ensuring young people are linked to mental health services that can transition into young adulthood (such as Headspace) provides a safety net for future years.

Research has demonstrated that the factor most closely associated with good mental health outcomes among care leavers is having safe, stable and affordable housing.

Working with a young person who has youth justice involvement

Adolescence is the peak risk time for offending behaviour from a lifetime perspective due to the developmental characteristics of this stage of life. (Refer to Neural development.)

According to a report conducted by the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare in 2017, young people in care were 19 times more likely to also be under the supervision of youth justice compared to the general population of youth. Indigenous Australians are 16 times more likely than the non-Indigenous population to be both in the child protection system and under youth justice supervision (AIHW, 2017).

These statistics do not imply that most young people who have had a history of abuse and neglect engage in criminal activity, but rather that a large proportion of young people who have offended have a history of abuse and neglect (Darker, Ward, & Caulfield, 2008; and CREATE Youth Justice Report, 2018).

Ensure that transition to adulthood planning is co-ordinated and aligned with youth justice case plans. With the consent of the young person, include youth justice staff as part of the safety and support network.

Working with young people who engage in high risk behaviours

Young people can sometimes engage in high risk behaviours such as problematic substance abuse, antisocial or criminal activities, self-harming, thinking about or attempting suicide, or frequently going missing from their care arrangement.

During periods of increased risk and complexity like this, a high intensity response can provide an intensive, seamless, wraparound safety and support plan to young people and families during periods of increased risk and complexity.

A high intensity response will be generated and coordinated by the young person’s existing safety and support network and any required co-opted members, to respond to:

- immediate safety concerns

- high complex needs

- high risk behaviours.

Network members engaged in a high intensity response often undertake joint action to achieve a particular goal with the young person or family. A willingness to share resources, including financial, practical and timely, is important. The approach of working together—closely collaborating with a sense of immediacy or sharing tasks—adds value to the support being provided to the young person or family on several levels, including:

- it reinforces the sense of wrapping around of the young person or family in a supportive environment, and reinforces the core value of relationship

- it makes it more likely that safety and support network members will be able to support each other in relation to the crisis nature of the work, the high risk behaviours of the young person and the complex and at times difficult decision making

- it enables greater sharing of skills, information and resources

- it can help ease the pressure for young people of interacting with only one worker and allow choice in relation to different network members

- it can provide a consistent response, creating a sense of containment for a young person or family.

Further reading

To deepen your understanding of providing a high intensity response, read the practice guide Safety and support networks and high intensity responses.

When the young person is transitioning to adulthood, careful thought is required to develop a safety and support network that will be sustainable into adulthood. This is an important time to revisit relationships with parents, siblings and extended family members, who while they may not have been able to meet a child’s needs when younger may have support to offer as they get older.

Where a young person has required a high intensity response as they approach adulthood, the network ideally will develop the ability to respond as needed without reliance on Child Safety to initiate and co-ordinate. Providers of professional and other services that are part of the network will gradually include those able to provide services beyond 18 years, such as Next Step Plus.

Young people who access Next Step Plus may also wish to choose a natural mentor to support their transition to adulthood. This informal mentoring role may be undertaken by someone in the safety and support network or they can become a member. Where a mentor has been chosen by the young person, this ongoing role can lead to increased stability, continuity of support and advocacy for the young person throughout their transition.

Working with expecting and new parents

Young people in care or preparing to transition to adulthood face unique challenges in regard to teenage pregnancy and parenthood.

Research indicates that between a third and a half of young people leaving care are either parents when they leave care, or become parents soon after. McDowall (2009) found that of 471 young people sampled regarding their leaving care experience, 28% were already parents themselves (CREATE, 2017).

Many research studies have highlighted the experience of motherhood as meeting a need for a young person—such as a sense of belonging and security and a feeling of being loved by their baby. Motherhood is said to have brought a sense of purpose and the motivation to do well in the future.

Many young parents face levels of stigma, and this can be especially challenging for young people in care or who have left care. They already feel stigma related to being in care, and many young people have said this makes it hard for them to seek support.

The young age of parents and parental child abuse experiences are identified as risk factors for future harm to one’s own children. This means there can be a high likelihood that the children of those transitioning to adulthood will end up with involvement in the child protection system.

Practice prompt

When working with young people transitioning to adulthood who are expecting or are new parents:

- Ensure you have a balanced view of the risks and resilience of young people. They may be experiencing struggles, but they may also be experiencing rewards from parenthood (as all parents do).

- Don’t stigmatise young people or make assumptions about their capacity to care for their children. Talk to them about their worries, feelings and hopes for their children.

- Ensure they have access to holistic support services including practical, therapeutic or financial resources.

- Establish a strong safety and support network for the young person. Parenthood can be isolating.

- Ensure young fathers are given the opportunity to engage with the parenting process.

- Consider if a more gradual transition process is possible if the young person has a supportive relationship with a foster carer who is supporting them in caring for their child.

Note

(The worker) said to me it’s such a shame seeing kids who grew up in care having kids so young … let’s hope he doesn’t end up in care too (young woman aged 26 years).

I’m always very cautious about everything I do with my kids … I’m afraid (the department) will try and remove my kids … by using my past against me. (Young woman aged 24 years.)

(CREATE, 2017).

Published on:

Last reviewed:

-

Date:

Maintenance

-

Date:

Maintenance

-

Date:

Maintenance

-

Date:

Maintenance

-

Date:

Maintenance

-

Date:

Maintenance

-

Date:

Maintenance.

-

Date:

Page created

-

Date:

Page created