Indicators

Child sexual abuse often occurs in the context of other forms of child abuse or neglect, including households where domestic and family violence is present (Howe, 2005; Hume, 2003). Hence, indicators may be subtle and attributed to other concerns or problems that the child may be experiencing.

Children who have been sexually abused can experience a range of physical, behavioural and emotional symptoms, including significant changes in a normal development, behaviour or demeanor, that may indicate trauma and sexual abuse (Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse, vol. 4, 2017).

Attention

Many children and young people do not disclose child sexual abuse they have experienced until they are in adulthood. Some children never disclose. Findings from the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse Final Report, vol. 4 (2017), found that on average, it took survivors of child sexual abuse on average 23.9 years to tell someone about the abuse.

Aside from a child’s verbal disclosure of child sexual abuse, indicators of sexual abuse can include:

- general trauma symptoms

- sexual behaviours that are inappropriate for a child’s age or developmental level

- a pattern of events, environment or behaviours that appears focused on keeping secrets

- sexual abuse can occur where there is bullying and intimidation of older children over younger children and where there is a power imbalance of some children over other children, who may even be the same age.

More specifically, indicators can be grouped into physical, behavioural (sexual and general) and emotional indicators (Mangilio, 2009; Righthand et al, 2003; Sanderson, 2004).

| Physical indicators | Emotional indicators | Behavioural indicators - Sexual | Behavioural indicators - General |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Sudden changes such as:

|

Children may engage in any of these behaviours by themselves, with other children, adolescents or adults, or in groups.

|

|

Attention

Always take a child’s verbal disclosure of sexual abuse seriously. A child does not need to exhibit any of the above indicators of child sexual abuse for their disclosure to be believed.

The presence of any indicators – except disclosure which is highly reliable in its own right - should not be considered in isolation. There may be several explanations aside from child sexual abuse to account for some behavioural presentations such as developmental delay and disability, a medical issue, other types of abuse or trauma and cultural considerations. Attempts should be made to gather as much ‘pre-abuse’ functioning information to accurately consider the child’s presenting behaviour.

Pre-abuse functioning includes consideration of the child’s:

- temperament

- attachment

- cognitive development

- emotional development

- mental health history

- psychological development

- psycho-social development.

Barriers to disclosure

There are a range of reasons why children and young people do not disclose, even when there is physical evidence or an admission of offending by an alleged abuser. These include but are not restricted to:

- the person who has experienced sexual abuse, or other family member, feeling guilty, fearful, embarrassed, or ashamed

- a lack of language skills to communicate the abuse

- a fear of not being believed

- fear of retribution

- afraid of threats made by the alleged abuser or a significant other

- fear of things getting worse due to an adult’s intervention or past negative experiences

- system and community responses, such as fear of what will happen following the disclosure

- trauma – the severity of the abuse, being unable to remember the details of the abuse

- dissociation, which can occur:

- during the interview or engagement with the child, thereby restricting the practitioner’s ability to obtain information

- during the abuse, which impacts the child’s ability to remember or articulate the memory of the abuse

- inability to recognise the activity as abusive

- cultural considerations (further outlined below)

- not wanting to talk to strangers

- the gender of the interviewer

- lack of parental support, either explicitly voiced or implied

- lack of confidence in adults and their ability to help.

(Alaggia et al, 2017; Moore et al, 2015; DeVoe and Faller, 1999; Faller, 2003; London et al, 2008; Paine and Hansen, 2002)

Children who have experienced sexual abuse need practitioners to:

- notice their distress

- recognise when they are conveying that abuse has occurred

- actively listen, show children that they are interested and concerned and want to hear children’s thoughts, feelings and needs.

Note

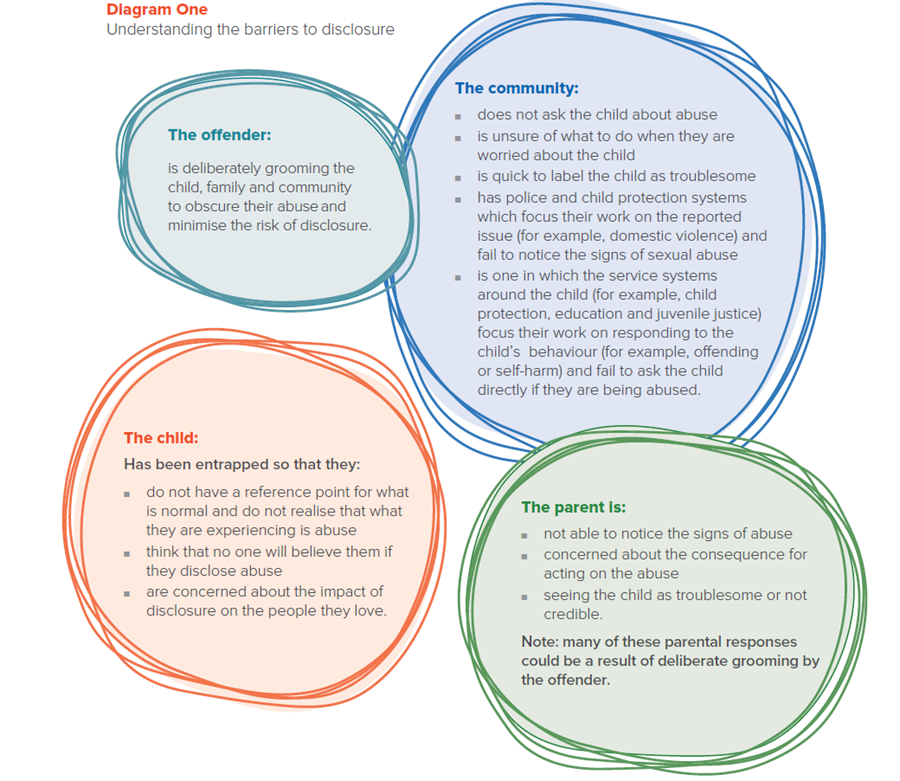

The below diagram has been adapted from Allnock and Miller’s (2013) article ‘No-one Noticed, No-one Heard’ which explored 60 children’s experiences of abuse in the United Kingdom. The diagram is a summary of their findings around why the sexual abuse of children does not stop sooner. It highlights common professional pitfalls in working with child sexual abuse, including instances where a committed offender has contact with children and families.

Note

It is acknowledged that the diagram contains the word ‘grooming’ which is commonly referred to as ‘manipulation and coercion’ by Child Safety in current practice.

Recantation

Children who disclose sexual abuse may at a later stage retract or recant their statements. Research indicates that exposure to familial pressures influences recantation - children are less likely to recant their statements when family members expressed belief in the children’s allegations and were more likely to recant when family members expressed disbelief in the allegation and the alleged abuser was still involved in their lives. (Malloy, et al. 2016)

The responses by professionals and others to whom children disclose their experience of sexual abuse also influences recantation. In a 2013 UK study of 60 young adults who experienced childhood abuse, including sexual abuse, 80% of the children who were sexually abused attempted to disclose the abuse. While some of the disclosures led to protective actions, others were not ‘heard’ or acted on there were a number of children who were made to meet with professionals and the alleged abuser and/or parent, who was complicit in the abuse. A number of these children recanted their disclosures and went on to suffer further abuse. (Allnock and Miller, 2013).

The Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse (2017) reported that studies indicated children who retract their disclosures or sexual abuse often later confirm their original disclosure.

There are several reasons why children recant their disclosures and their recantation should be considered in the context of all information gathered during the investigation and assessment. A child’s recantation may be due to:

- pressure from the perpetrator, family or others

- concern about negative personal consequences, such as fear of the perpetrator or causing distress to loved ones

- investigations by police or child protection services, including videoing disclosures

- criminal proceedings.

- the upheaval created since the investigation and assessment commenced or since they first disclosed (for example, they may have seen the alleged abuser leave home or the child may have been removed from the home themselves)

- observing how others have been affected (for example, the child’s parent may have had to rejoin the workforce or leave the workforce, they see their parent upset)

- fear that others will (or have) blamed them or had other negative reactions to them (including siblings, grandparents, parents)

- fear of retribution from the alleged abuser

- an ongoing concern for the alleged abuser which may be due to the child’s relationship with the abuser (who could be the child’s parent or family friend).

These factors can influence a child to recant their disclosure. Their impact may be subtle in how they influence a child making such factors difficult to detect and manage.

Note

The level of support provided to the child by the parent/carer is of paramount importance in reducing the likelihood that a child may recant. Ensure that a parent/ carer has appropriate education and support for a child in their care who has disclosed sexual abuse.

Further reading

Read the New South Wales Office of the Senior Practitioner Child sexual abuse and disclosure What does the research tell us? (2014) to understand more about what children need to help them to disclose.

Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse Final Report, vol. 4 (2017).

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples have been treated differently under past government laws and policy than other Australians, including systemic racial discrimination and genocide and forced removal of children (simply for the cultural group they belong to and past legislation that had deemed children born to Aboriginal mothers as children being neglected and in need of protection (Industrial and Reformatory Schools Act 1865). This has caused intergenerational trauma which continues to have implications for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families today.

The sexual abuse of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children should be viewed in the context of the historical impacts from colonisation. The legacy of intergenerational and collective trauma combined with the fact that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children come into contact with child protection and juvenile justice settings at disproportionate rates has led to mistrust and fear of statutory authorities. The implication for practice is that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children are less likely than non-Indigenous children to disclose to police or child protection practitioners in formal interviews.

There are additional barriers to disclosure identified in the literature relating to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children disclosing sexual abuse:

- fear that reporting sexual abuse will result in the authorities intruding into their family and community or the child (and possibly their siblings) being removed from their family

- fear that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children who report being sexually abused by white adults, will not be believed

- general fear that because they are Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander, they will not be believed

- reluctance to disclose or report sexual abuse due to previous experiences of injustice and negative experiences with service providers (including being denied their cultural identity through disrespect of, or suppression of, culture and having limited or no contact with siblings, family and community)

- disclosure is hindered by lack of culturally safe sexual assault services and Aboriginal-specific sexual assault services (Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse Final Report, 2017)

- isolation from service providers in remote communities

- a lack of community understanding about child sexual abuse and how to address it

- lack of culturally specific sex education for children in schools

- shame experienced by children and their families

- fear of reprisals from the alleged abuser and their families due to how disclosure will impact family and community networks (Aboriginal Child Sexual Assault Taskforce, 2006; Gordon et al., 2002; Mullighan, 2008; Wild and Anderson, 2007, as cited in Anderson et al., 2017).

If an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander child does not disclose sexual abuse during a formal interview, do not assume that the abuse has not occurred. All children, including Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children, are more likely to disclose sexual abuse if they have access to adults who they feel safe with, who they know believe them, and who they trust to protect them.

Culturally appropriate care promotes a child’s wellbeing. For Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families and communities, the sharing of parenting roles, nurturing and socialising responsibilities is the cultural norm. At the heart of a collectivist approach is the safety and wellbeing of all children belonging to the community. Having access to a wide range of support when they experience difficulties increases the protective factors for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children by increasing the number of secure attachment relationships that they have in their extended kinship network (Lohoar et al, 2014). If a child discloses sexual abuse, practitioners can aim to ensure the child’s connections to secure attachments and important relationships continue wherever possible.

As practitioners, develop and respect cultural and community norms regarding who is appropriate for a child to speak to about sensitive topics, and the timing and context of these conversations. Make arrangements for a trusted support person (preferably someone who is the same gender and is from their family or kinship group) to support the child during interviews and to support the child in responses that follow the child’s disclosure.

Strong cultural connections increase protective factors for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children by supporting the social and community conditions required for adults to heal their own trauma, foster strong attachments to children in the community, and in turn, create safer more connected communities (Anderson et al, 2017). Increasing the presence of protective factors in an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander child’s life may not guarantee they are protected from abuse but may reduce the likelihood of them being sexually abused. Protective factors include the child having:

- supportive and trustworthy adults

- supportive peers

- an adequate understanding of appropriate and inappropriate sexual behaviour, including sexual abuse, and personal safety

- the ability to assert themselves verbally or physically to reject the abuse

- the ability to be self-confident and know how and when to disclose abuse

- strong community or cultural connections

- culturally appropriate care, if living in care.

(Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse Final Report, 2017)

Further reading

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children and child sexual abuse in institutional contexts.

Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Sexual Abuse Final Report, vol. 3 (p.130-133) (2017).

Read further about 'Women’s business and men’s business' and 'Understanding the concept of shame' in the Working with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families section of the practice kit Safe care and connection.

Culturally and linguistically diverse children

For families from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds, there may be additional considerations regarding a child’s disclosure of sexual abuse. For migrant and refugee children and families, the journey from their country of origin to Australia can vary from a planned trip to a journey that was unforeseen, sudden, dangerous and exhausting.

Women and children of culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds face a range of additional barriers to reporting violence and sexual abuse, which are further outlined below. This may lead to women and children being hurt and sexually abused over a long period of time and the violence or abuse becoming more severe. The family system may appear more closed and protective of the person responsible for the abuse due to broader cultural or community isolation, rejection, fear or stigmatisation.

While culture cannot and should not be used as an excuse for the abuse of children, some newly arrived migrants and some members of established communities may be unfamiliar with aspects of Australian legislation, including legislation relating to child protection. For some people from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds, there may also be different views about what constitutes child abuse and neglect in their country of origin. This does not mean that the welfare and interests of the child should not be paramount in all decisions but rather, differing approaches to parenting and a lack of understanding or appreciation of norms expected in Australia could be factors that are encountered during assessment and case work and need to be responded to.

Factors impacting family engagement and responses

Many factors for a cultural diverse child and their family can impact how they engage with Child Safety and other services in relation to child sexual abuse, which are outlined below.

Compromised visa status

If child sexual abuse allegations lead to charges and conviction, visas for the individual or family may be impacted. There are financial and emotional impacts resulting from a decision to leave a partner who has sexually abused a child, and a parent may be less likely to adhere to any safety plan for a child which means an alleged abuser must leave the family unit.

Social isolation

An absence of a support network compounded by lack ofculturally and linguistically diverse services may lead to a family becoming a ‘closed network’, with limited opportunities for children to disclose abuse. A lack of knowledge about support services, or a mistrust of services due to past experiences, may prevent a parent from seeking help for their child. Due to this isolation and invisibility, children from culturally diverse families are under-represented in child protection notifications.

Note

Limited understanding of Australian laws around harmful cultural practices

A family may have a limited understanding of Australia’s laws around cultural practices such as female genital mutilation/cutting and forced marriage.

Female genital mutilation/cutting is the deliberate cutting or altering of the female genital area for no medical reason. It has many names, including cutting, female circumcision and ritual female surgery. Female genital mutilation/cutting refers to all procedures involving partial or total removal of the external female genitalia, or other injury to female organs (such as stitching of the labia majora or pricking of the clitoris) for non-medical reasons. Globally, there is a link between female genital mutilation and other harmful practices such as early and forced marriage. Female genital mutilation/cutting is illegal under the laws of Australia’s States and Territories. This includes sending a person overseas to have a procedure done, or facilitating, supporting or encouraging someone to have this done. A girl at immediate risk of female genital mutilation/cutting may not know what's going to happen, but she might talk about the following or you may become aware of:

- a long holiday abroad or going 'home' to visit family

- relative or ‘cutter’ visiting from abroad

- a special occasion or ceremony to 'become a woman' or get ready for marriage

- a female relative being ‘cut’ – a sister, cousin, or an older female relative such as a mother or aunt.

Tip

The practice of female genital mutilation or cutting is a crime in all states and territories of Australia. This includes sending a person out of the state or overseas to have a procedure done, or facilitating, supporting or encouraging a person to have this done (Criminal Code Act 1899, sections 323A and 323B).

A forced marriage is when a person is married without freely and fully consenting. Children may have been coerced, threatened or deceived, emotionally pressured by their family, been physically harmed or threatened with harm or tricked into marrying someone. A person under 16 years of age at the time of the marriage is not usually considered to be capable of understanding the nature and effect of a marriage ceremony.

Note

It is a crime in Australia to cause a person to enter into a forced marriage or to be a party to the forced marriage (unless you are the victim), including by force, threat or trick. This includes legal, cultural and religious marriages. (Commonwealth Criminal Code Act 1995, Division 270.)

In Australia, a range of factors may indicate that a child is at risk of a forced marriage, including if the child:

- suddenly announces they are engaged

- suddenly leave school or are away from school for a long time with no reason

- indicates they will or actually does run away from home

- has older brothers or sisters who stopped going to school or who were married early

- is never allowed out or always has someone else from the family with them

- shows signs of depression, self-harming, or abuse of alcohol and other drugs

- seems scared or nervous about an upcoming family holiday overseas

- exhibits indicators that they are experiencing family violence or abuse.

Gender roles

Gender roles and attitudes to family roles and responsibilities, domestic and family violence, sexual assault and children may be influenced by the belief that men are superior to women. Families may be unaware of how violence and sexual abuse is defined in Australia, and this impacts on the disclosure of child sexual abuse and actions to keep children safe. When assessing a child’s safety, focus on whether power and control are misused within the family, resulting in an alleged abuser having access and opportunity to sexually abuse a child.

Community reputation of an alleged abuser

Patriarchal cultures where men’s voices are valued over the voices of women and children can create barriers to disclosure. These barriers may include fear of reprimand, fear of not being believed or of being discredited, and being disowned and isolated. These worries can have significant implications on a child’s disclosure, family’s response, and the child and family’s engagement with the criminal justice and child protection systems.

Language barriers

The alleged abuser may be the only person who speaks English in the home, which significantly impacts on:

- a child’s ability to disclose to someone who they trust and who understands them

- a parent’s ability to act independently in relation to keeping a child safe.

When considering the use of an interpreter, seek information about cultural factors and gender roles that impact on the choice of interpreter. Due to the sensitive nature of child sexual abuse, determine if the interpreter is willing to translate the content of child sexual abuse in a way that their beliefs and values do not influence the translation.

Attention

Be aware that connection to cultural community will vary from family to family and some people have multiple cultural influences, customs and languages. Children who have parents from multiple cultures or countries require practice to be culturally responsive to both cultures (Fontes and Plummer, 2010).

Culture as protection and strength

Do not stereotype or make assumptions about a family’s functioning based on their cultural or linguistic background. The family are the experts of their culture, so start with the family to ask questions to understand and acknowledge cultural differences and norms. This is a good way to engage with and empower the family.

Culture can be a protective factor. Cultural communities and networks may provide support and refuge for women and children hurt by violence. Practitioners may be able to draw on community or religious leaders to challenge a man’s sexual abuse of a child, remaining mindful of community attitudes towards the victim around the disclosure. Cultural practices or faith may be a form of resilience that the mother or child may draw on to survive the sexual abuse and give them hope.

Being connected to extended family and culture is also a protective factor for children. A strong sense of culture can strengthen a child’s self-esteem, sense of identity and belonging. Children who are not connected to family and are not visible in or supported by their communities are more vulnerable to harm.

Further reading

Towards estimating the prevalence of female genital mutilation/cutting in Australia, (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2019)).

Female genital mutilation, National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children (2021).

Forced and early marriage factsheet (2019), Department of Social Services.

Anti-Slavery Australia has resources about forced marriage on the My Blue Sky website.

Additional information is available on the Immigrant Women’s Support Service for immigrant and refugee women from non-English speaking backgrounds and their children who have experienced domestic and family violence.

How child sexual abuse is discovered

Children’s disclosures of child sexual abuse are seldom straightforward and are often indirect and accidental. Children may alert adults to the fact they have been or are being abused through:

- making ambiguous verbal statements

- changed behaviour

- increased risk-taking behaviour (self-harm, suicidal behaviours, disordered eating)

- beginning to say or do sexual things inappropriate for their age

- some disclose after participating in an intervention or educational program

- some initially deny or say they forget only to disclose later

- some disclose but retract later

- some say they made a mistake, lied or the abuse happened to another child.

(Australian Institute of Family Studies, 2015.)

Child sexual abuse can become known about in four main ways:

- a voluntary, complete disclosure from the child

- a voluntary, incomplete or partial disclosure from the child

- the sexual abuse is discovered

- the sexual abuse is suspected.

(adapted from Lanning, 2002, p.333).

A voluntary complete disclosure is when disclosure occurs voluntarily by the child or young person. They have told another person of the abuse they have experienced and are able to relay the details, with varying degrees of complexity and completeness (dependent upon their age and other barriers that may exist). This child or young person can generally be supported to provide detail with little intervention required by the departmental officer or the police. While these children or young people provide a lot of detail, it is still important to conduct the interview in such a way that enough detail is generated to assess risk and protective factors.

Note

Some of the barriers to disclosure may become apparent once other people are aware of the child sexual abuse allegations. In some cases, other people becoming aware of the abuse can lead to recantations later on.

A voluntary but incomplete or partial disclosure occurs when the child or young person may be unable to or chooses not to reveal the full details of the abuse (Faller, 2003). Information about the abuse is either not recalled or not provided completely due to the barriers to disclosure (identified in the section above). It may also be that a child has disclosed the sexual abuse once and will not disclose tell again because the response they got from the original disclosure was not positive, or there was no change to the abusive behaviour after disclosure.

When sexual abuse is discovered, the sexual abuse becomes known to others. This occurs when either the alleged abuser or the child is observed by another person, either through medical examinations (due to specific or non-specific complaints of symptoms) or when physical evidence such as pictures, videos or blood on underwear are discovered.

Sexual abuse that is suspected presents the greatest challenge for practitioners, as the issues requiring investigation and assessment are difficult and complex, and require sensitive, skilled interviews. Practitioners must balance the child’s reluctance to talk about sexual abuse with the possibility that they were not abused. Consideration should also be given to the embarrassment and confusion a child may be experiencing about the sexual abuse and being asked personal questions about their body and abuse by strangers in formal settings.

To further understand the ways in which children disclose or convey their abuse including help-seeking behaviour, telling without words, partially telling, telling others and telling in detail, refer to Noticing and responding to the child's disclosure in the Recognising disclosures and responding to children section.

Published on:

Last reviewed:

-

Date:

Maintenance

-

Date:

Maintenance

-

Date:

Maintenance

-

Date:

Maintenance

-

Date:

Maintenance

-

Date:

Page created

-

Date:

Page created

-

Date:

Page created

-

Date:

Page created