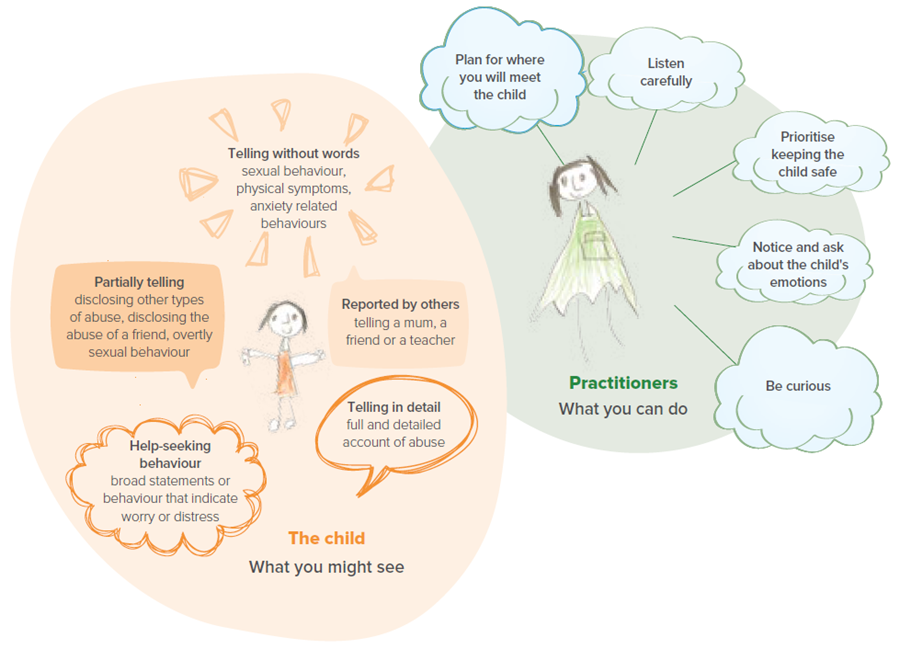

The following diagram provides a summary of the different ways a child may try to tell practitioners about their abuse, as well as how to support the child to speak out. There is further detail in the remainder of this part.

Note

Young children may use words in ways not used by adults or use special words to describe things. For example, they might refer to semen as ‘white glue’.

Children may also use the words in their vocabulary to describe a situation even when the choice of words may not be considered appropriate or relevant by adults. For example, a child described being ‘stabbed’ even though there was no evidence of a knife or any injury. The description was simply meant to convey the pain involved in the sexual abuse rather than suggest the use of an instrument (The Australian Institute of Judicial Administration, 2020).

Disclosure takes time and for many children it is a process. Current research shows that practitioners who are warm, curious, notice children’s emotions and ask directly about abuse are more likely to help a child talk about their abuse (Malloy, Brubacher and Lamb, 2013; McElvaney, 2015; Paine and Hansen, 2002). A child does not always disclose sexual abuse verbally. There may be physical, emotional and behavioural indicators present, and it is up to the adults in contact with a child to pick up on non-verbal clues that sexual abuse is occurring, and for them to be proactive in providing an environment in which a child feels safe to tell. See ‘Responding to children who are telling you about their abuse with non-verbal cues’ below in 'Notice and respond to the child's disclosure'.

Tip

Child Safety’s role is to help keep children safe. Practitioners can do this by supporting a child to talk about what is happening in their lives - not to prepare evidence for criminal court or catch an alleged abuser.

Work alongside the Queensland Police Service in a criminal investigation

When working alongside the QPS in a criminal investigation, some practitioners are unsure how to communicate with a child or family. These fears can come from a desire to make sure questions do not hinder a criminal investigation or impact on the child’s credibility during a criminal justice process.

Attention

Wherever possible, work with the QPS to be part of interviews with the child under the Evidence Act 1977, section 93A.

If Child Safety have not been part of the interview process, it can be challenging to work with a family in a way that does not hinder a criminal investigation. Child Safety and the QPS can usually work together to plan what statements about the abuse can be used; for example, ‘We know we can’t talk about the specific allegations that (child) has made but we can talk about how something very serious has happened and we need to make a plan about how we keep (child) safe from further abuse, and how we keep (alleged abuser) safe from further allegations’.

It may be a concern to the QPS and Child Safety that child protection work or therapeutic work may impact on the child’s credibility during a criminal justice process. Child Safety plays an important role in providing support for children and families who make statements to police about abuse. Not all disclosures lead to prosecution and as practitioners, our primary role is to ensure the child’s safety, belonging and wellbeing. If prosecution outcomes are prioritised over the safety of children, we inadvertently run the risk of not hearing children’s worries and may lose opportunities to build a relationship with the child and help keep them safe.

When the QPS have concerns about Child Safety talking to a child or family about abuse allegations, practitioners can take a creative approach to working with the family and acknowledge that there may be limitations on the details of the allegations that can be discussed. Practitioners may not be able to ask specific questions about the abuse, but can still strongly advocate the child is provided with therapeutic support if they need it. The focus of any therapeutic work can be around emotional support to address the upheaval in the child’s life as a result of abuse and police involvement. Safety planning can still be completed with a family. Support for working alongside the police can be established through regular conversations with the lead police officer, SCAN team referrals and meetings or by regular stakeholder meetings.

Interviewing techniques

Common questioning structures or techniques used when talking to or interviewing children include ‘open ended questions’, ‘free narrative’ and ‘leading questions’. Each has its own strengths and limitations.

Free narrative and open ended questions

Open ended questions do not assume a particular answer. When talking to a child, the use of open ended questions can support them to provide a free narrative account about a topic. Free narrative allows the child to talk as much as possible about a topic in their own words, before a practitioner asks them more specific, closed or leading questions to obtain further information. A child is less likely to make something up or ‘guess’ an answer to please the person interviewing them if they are providing free narrative. Open ended questions that support free narrative are usually requests for more details about events already mentioned by the child. They usually follow, or are part of, the initial free narrative stage of an interview.

It is good practice to build a relationship with a child and begin a conversation by using open ended questions. Open ended questions can focus on the child’s emotions, the things they like or don’t like about something or someone, or they can be used while completing the three houses tool (to name a few approaches).

Tip

Examples of open ended questions / statements:

- Can you tell me what you’ve been up to this week?

- Tell me all about your father…

- You said before you felt scared - What happens when you feel scared?

Once rapport is built, practitioners can use open ended questions to explore the child protection concerns. If the child has talked about the things they enjoy doing with their mother and the worries relate to concerns about their father, the practitioner may then say “You told me before about the things you enjoy doing with your mother. Can you tell me about all the things you do with your father?” This questioning style can then continue with the practitioner asking the child “What else?”, “And then what?”, “What happens next?”, before returning to an important topic to ask more specific questions once a child has finished their free narrative account. For example, “You said before that John made you go into his room - What happened next?”.

Tip

Leading questions

In the child protection context, a leading question is a question that directs the child towards an answer, rather than allowing them to independently introduce the topic. A leading question asked by a practitioner might suggest a certain answer or assume the existence of facts that have not yet been mentioned by the child (although the child may have previously discussed these facts with the notifier or similar). Examples of leading questions:

- You were scared in the car with dad, weren’t you? (This can encourage a child to agree with a practitioner’s suggestion that they were scared).

- Can you tell me about when your brother touched your vagina? (This assumes that the child’s brother in fact touched her vagina).

Be aware of both the risks and benefits of using leading questions when working with children. Leading questions can impact the information a child gives practitioners, because the child may be reluctant to contradict or correct the adult they are talking to. Leading questions can also help children. They can support a child to stay on track, help them understand why you are speaking with them, and give them permission to talk to you about the abuse.

Tip

Practitioners may also use a leading question or leading statement to clearly explain why they are worried and why they have come to talk to the child. For example, if a child has attended school and disclosed sexual abuse to their teacher, as part of the interview process it could be appropriate to say to the child, using their words, “I’m here to talk to you about what you told Mrs Brown- That your father made you touch his doodle”.

Note

Some children don’t use anatomically correct names for their body parts. Furthermore, alleged abusers can intentionally use other words for body parts or abusive acts to make it difficult for a child to disclose what is happening. Use a child’s own words or phrases when talking with them and take time to understand and clarify the meaning of a child’s words or phrases.

Sometimes a child might provide a ‘yes’ or ‘no’ response to a question. If a child gives a ‘yes’ or ‘no’ answer without an open narrative or further elaborating on their response, the child may be feeling uncomfortable, trying to please or trying to avoid the discussion. Young children may also believe that any question asked of them should have an answer, and may provide an answer without understanding the question. This does not mean that the abuse did not happen. Continue to build trust and engage with the child talking about their friends or hobbies, and return to specific questions about sexual abuse later.

Tip

Children need to have a good understanding of your worries before you end a conversation with them. Ensure the child understands the purpose of your discussion with them and what is going to happen next. This helps prevent the child from ‘filling in the gaps’ themselves with incorrect information and may also help them to feel more comfortable to talk to you about their abuse at another time.

Supporting the child to talk about the abuse

Most victims of sexual abuse in childhood are abused by people they were close to, people who were trusted by the child, their family and community. Within this context of close, trusting and interconnected relationships between the abuser, the child, the parents and the community, it can be incredibly hard for children to speak out about their abuse.

Children do not generally have conversations using a question and answer format. Instead, they like to introduce their own topics, ask their own questions and express how they feel. They can have difficulty staying ‘on track’, answering the questions that are asked of them, and can have problems waiting for their turn to speak (The Australian Institute of Judicial Administration Incorporated, 2020).

The concepts for supporting disclosure in this part are creative and child-led; they aim to provide an environment that is comfortable and familiar for the child and allow them to tell their story in a way that feels natural to them. These concepts can be used to build trust with the child and help them to tell their story in free narrative form. You can then use the “who”, “what”, “where”, “when”, “why” and “how” questions to drill down into the child’s narrative (The Australian Institute of Judicial Administration Incorporated, 2020).

Practice prompt

Introduce the concepts for supporting the child to talk about the abuse to the people they have a relationship with, for example, community members, parents and professionals who know the child (the child’s safety and support network). (Refer to the practice guide Safety and support networks and high intensity responses.)

These people may be uncomfortable broaching sensitive topics with the child and may need Child Safety’s permission, guidance and support to help the child to disclose to them and to support the child.

Attention

Speaking out about sexual abuse takes time. Multiple conversations with someone who the child can build rapport with helps them feel safe and supported to tell their story and can assist with accuracy and a more detailed account of the abuse. One study observed that 95 per cent of children had disclosed new information by the sixth session (Esposito, 2014).

The ideas in this table focus on practices which help to build a relationship and connection with a child and helps them to tell their story.

|

Practice considerations |

Conversation ideas |

|---|---|

|

Children are likely to respond with more trust and openness to practitioners who are:

|

“You looked upset when I talked about [alleged abuser]. Tell me about that.” “I talk to lots of kids about their worries. It can be tough telling someone like me about your worries but I might also be able to help.” |

Ask the child if they:

|

“I need to talk to you and ask you some personal information. Where would you like to go?” “Sometimes, kids like to talk while we go for a walk. Would you like to do that?” |

|

Take your time. It can be difficult for children to speak out about sexual abuse, especially to a child protection practitioner they have never met before. Take time and prioritise building a connection with the child. Even if the conversation seems to be going off track, follow the child’s lead. Humour and play in the midst of a difficult conversationor talking about the child's interests can provide the child with time to become calmer and organise their thoughts. Return to your planned conversation later. It may be appropriate to return to speak with the child again. It can take a number of interactions to build a relationship. Be careful about continuing to question a child who looks distressed, uncomfortable or is giving mono-syllabic answers. Instead acknowledge what you see, give the child a short break and come back to the question once the child is more settled. |

“Sounds like Jack doing a silly dance in class today made you laugh a lot. What else makes you laugh? When was the last time you laughed a lot? Who else was there? What did they do and what did you do?” “I am worried about you. I really want to help you with those upset feelings.” |

|

Listen to the child and remain open by:

|

“It sounds like things are really tough in your family. I can see it makes you sad and worried. What other things are making you worried at the moment?” “Are there any other worries you would like to talk about?” |

Practice prompt

Emotions are contagious. Help a child remain calm by staying calm and centred yourself. This is a good example of co-regulation.

If a child becomes distressed, exaggerate slow, calm breathing and try to avoid talking. You can continue to use facial expressions and body language to show the child that they are cared for.

When talking to a child about sexual abuse, practitioners may already have some ideas about the identity of the alleged abuser. These ideas can be helpful but may also make it hard to listen to the child’s experience of abuse, or be open to alternate hypotheses. This is particularly true when the child is describing an alleged abuser who is not an adult male or is someone in a position of authority in the community. Listen carefully to the child and maintain an open mind, being guided by the child.

Further reading

Read the Working with young people at risk of sexual exploitation section of this practice kit for ideas on identifying and responding to sexual exploitation.

Support a child with disability to disclose abuse

While the extent of sexual abuse of children with disabilities is not known, research suggests that up to 14% of children with disabilities in Australia are likely to experience sexual abuse (Llewellyn, Wayland and Hindmarsh, 2016). There is strong evidence that sexual abuse of children with disability goes largely undetected and often underreported. Children with disabilities struggle to disclose sexual abuse at higher rates than children without disabilities and that delays in disclosure are common (Esposito, 2014).

Parents of children with disability report that when they raise concerns about their child with disability having been abused or are being sexually abused, they are often dismissed or the child was labeled as the problem. (Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse (2017).

Reasons for low disclosure rates include:

- problems communicating

- feelings of guilt and deep shame

- Fear of getting into trouble

- Fear of not being listened to or believed (often a past history of this)

- feeling worried about being abandoned or separated from family

- a reliance on the abuser to meet their daily needs

- a willingness to tolerate abuse to be accepted

- limited understanding of protective behaviours and a lack of knowledge and skills needed to escape unsafe situations.

- Not understanding their rights to raise an issue

- Not understanding what has been done to them is wrong.

Children with disabilities are most often abused in care giving settings, including when receiving personal care by in-home carers, in respite care, foster care or residential care, at school, in after school care and during transport to and from school. Children with disability are also sexually abused by family or extended family. Their sexual offenders are most often male and girls are more likely to be sexually abused than boys. (Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse (2017)).

Difficulties disclosing abuse are compounded by the professional response to children with disabilities. Researchers from the UK found that children with disabilities were less likely to be referred to child protection services for sexual abuse. Researchers also found that even when children with disabilities were reported to child protection, there was a higher threshold for triggering a response. This was suggested as being due to practitioners:

- empathising with the stressors experienced by parents of children with disabilities

- believing that children with disabilities had positive support networks in place

- lacking the skills and confidence to communicate and work with children with disabilities.

Researchers concluded that the lack of research capturing the voice and experiences of children with disabilities , the lack of disclosure by children with disabilities, and the limited confidence and capacity of practitioners in this area mean that children with disabilities remain largely invisible to the system.

Practice prompt

When preparing to talk to a child with an intellectual impairment, understand that every child’s needs are different based on the functional impact of their disability. Talk to people who know the child best to understand the child’s intellectual or cognitive impairment, the impact this has on their comprehension, and their ability to communicate and recall information.

Remember to:

- Simplify your language. Use short simple sentences. Give one idea at a time. Avoid using complex or abstract concepts (such as date or time).

- Supplement your language with facial expressions and gestures.

- Check the child has understood by asking them to repeat what you have said in their own language. For example, "Why do you think I am here?"

- Give the child time to process information and respond to your question (30 seconds is quite normal - practice waiting for 30 seconds and be prepared to be patient).

- Use other communication strategies and visual tools to explain concepts.

- Rephrase information if the child does not understand.

Specialist Services and the Specialist Practice team can provide information and support about supporting a child with a disability to disclose child sexual abuse.

Further reading

Read the Working with a child with disability and Risk assessment sections of the Disability practice kit for further information on understanding common disabilities and ways to improve communication when engaging with a child with disability.

Read the New South Wales Office of Senior Practitioner Child sexual abuse What does the research tell us? A literature review (2016), Chapter 3, section 3.1.5, 'Victim, family and community-level risk factors associated with child sexual abuse’) for detailed information on the risk factors associated with a child’s environment, relationships and culture that create conditions under which abuse can occur for children with disabilities.

Read the Research report on disability and child sexual abuse in institutional contexts, Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse, Centre for Disability Research and Policy, University of Sydney (2016), for information about the extent of sexual abuse of Australian children with a disability.

Supporting children to make disclosures

Use books and other resources, such as videos or presentations, to prompt children to speak about their abuse and to reduce their silence and any shame they may feel about their abuse

Notice a child’s emotional distress and ask about it, which can help children to disclose. You may discuss your own emotions, such as worry for the child, and use this to engage with the child and demonstrate your concern for them. For example, “You look really upset right now, can you tell me about that?”

Recognise that children from some cultural groups may need more time to be comfortable talking about how they feel. Talk to a practitioner from that child’s culture to develop appropriate conversation ideas and understand more about cultural considerations for the child. Some children from diverse cultural groups may feel more comfortable having a trusted person from their culture (or religion), such as a friend or professional, present at the meeting, who understands the cultural practices and norms that may affect disclosure and reporting of the child sexual abuse.

Find out about the child’s interests and bring items to your meeting that you think or know the child will be interested in. For example, funny pens or an interesting-shaped rock or flower.

Avoid wearing clothes that are too formal as this can be intimidating for children. At the same time, avoid clothes that are too informal, particularly clothes that are revealing as this can be distracting and uncomfortable for children.

Noticing and responding to the child's disclosure

“Sometimes kids will open up if they trust someone. But if no one’s talking to them and no one’s saying that they are here for you they are not going to say anything. No one told me they would listen”

– Tara, 18 years old, in ‘No-one Noticed, No-one Heard,’ Allnock and Miller (2013).

Children do speak out about their abuse, but these disclosures may not be noticed, believed or responded to appropriately. If they are not noticed or are met with a negative response or indifference, children may not talk about the abuse again for some time. This research shows how important it is for us to recognise when a child is disclosing and respond in a way that supports and validates the child.

The information in this section will help you to recognise when a child is trying to tell you about their abuse and how you can respond helpfully to them.

Practice prompt

Children rarely lie about being sexually abused. Children are more likely to disclose abuse to people they have a close relationship with and see often including mothers, friends and teachers.

When a child tells a professional, parent, friend or community member that they have been abused, consider it to be a credible account of what has occurred and take steps to keep them safe, even if they do not tell us directly in a follow up interview.

The five common ways that children convey their abuse:

- help-seeking behaviour

- telling without words

- partially telling

- telling others

- telling in detail.

Consider these different types of disclosure when conducting a file review to help notice possible signs of child sexual abuse that may not have been identified at the time.

Tip

Educate and support professionals, family and community members to build a strong connection to children, notice signs of abuse and respond to the different types of disclosure through the development of safety and support networks, which are vital in planning for safety for a child into the future.

Responding to a child seeking help through their behaviours

Children may not have the words to tell someone about their abuse. They might try to show that something is wrong by their behaviour, or by broad statements that show general worry or distress. These behaviours can be misinterpreted by adults or labelled as ‘difficult’ or ‘challenging’. This can silence the child further.

Children with disabilities who start to act out or behave in ways that are different and out-of-character from their normal behaviour may have experienced sexual abuse. Their behaviour may indicate their level of distress, including fear of the perpetrator, not knowing how to talk about the abuse or who to talk to. There is a risk their behaviour will be viewed as being part of their disability and the abuse may go undetected.

Common forms of help-seeking behaviours include behavioural and emotional signs. For example, changes in behaviour, acting out or being very quiet, emotional distress. The child may make verbal statements, for example ‘I do not like [alleged abuser ].’

| Practice considerations | Conversation ideas |

|---|---|

|

Ask about the behaviour and what might be going on for the child. Help the child to understand how their behaviour might be reflecting their emotional state. Be direct about the help-seeking behaviour and say why it worries you. |

“This behaviour isn’t like you. Is something making you angry at the moment?” “Sometimes kids get angry and hurt others because they are really sad. Is this happening for you?” “It sounds like you do not like [alleged abuser]. Can you tell me about that?” “You looked upset when I talked about [alleged abuser]. Your teacher also told me you really did not want to go home with him. Tell me about that.” |

Practice prompt

There will be times when you are trying to determine whether a child’s behaviour is ‘normal’ or related to child sexual abuse.

Read the Developmental and Harmful Sexual Behaviour Continuum at a Glance for more information to help to differentiate expected sexual development from behaviours that are concerning. This tool should be used carefully as it addresses sexual development in children more generally. Because it is designed to be broad, it does not fully address diversity such as the impact of religious or cultural beliefs and practices. It should therefore be used in conjunction with an understanding of the dynamics of sexual abuse as well as an understanding of the religious and cultural practices and beliefs of the family in question.

These questions can also help to understand the child’s behaviour:

- When did the behaviour first start?

- What was happening just before the behaviour started?

- Are there places that the behaviour happens most frequently?

- How many of the behaviours are occurring at the same time?

Responding to a child telling others through non-verbal cues

Some children may struggle to tell others in words about their abuse. This may be because of the developmental stage they are in, or they may be fearful or reluctant, or they may feel guilt and shame. For these children, non-verbal signs are important indicators that abuse may be occurring. As identified in Understanding indicators of child sexual abuse section of this practice kit, there are multiple physical, behavioural and emotional indicators that a child has been sexually abused. For example, soiling underwear, sore genitals, excessive masturbation, drawing sexual acts, nightmares, and regression. Consider these as part of a broader assessment rather than in isolation. The following practice considerations and conversation ideas provide examples of ways to approach a child’s behaviour:

|

Practice considerations |

Conversation ideas |

|---|---|

| Notice and ask about symptoms and behaviours. Help children to understand the link between their behaviour and their worries. |

“Can you tell me more about this picture? What is [alleged abuser] doing here? What is the girl doing here? How do you think this girl is feeling?” “Sometimes kids who have worries have more toileting accidents. Do you have some worries? Could you tell me about them?” |

| Be curious about what these behaviours or symptoms could mean. |

“I am glad I saw this picture. A picture like this makes me feel really worried about you. Can you tell me some more about what’s going on for you?” “Having a sore [vagina/penis] must be really uncomfortable. Can you tell me why you have a sore [vagina/penis] today?” |

| Directly ask the child about sexual abuse and talk about the information you have that has made you worried. |

“You showed me a doll lying on top of another doll. Have you seen people on top of each other? Has anything like this ever happened to you?” |

Responding to a child's partial disclosure

A child may make a partial disclosure about their abuse to someone because:

- they are testing to see how others react

- they do not have the language to describe their abuse

- they are fearful of providing others with a purposeful disclosure

- they are ashamed about being abused and unsure about disclosure.

Tip

Common forms of partial disclosure may include disclosing:

- other types of abuse, for example physical abuse, domestic and family violence

- the abuse of another child or young person

- that they are sexually active.

|

Practice considerations |

Conversation ideas |

|---|---|

| Acknowledge and respond to what the child is telling you, even if the child is not describing the incident that you are most concerned about. |

“Thank you for telling me that [alleged abuser] smacked you yesterday. I believe you. Can you tell me more about that?” |

| Ask about how the child responded to what they are describing. |

“What did you see that told you [alleged abuser] was cross? When you saw [alleged abuser] was getting cross, what did you do? It sounds like you really tried to calm [alleged abuser] down. Have you tried to do this before?”. |

| Notice and normalise the child’s emotions and ask the child about them. |

“Kids sometimes find it hard to talk to adults about their worries. Kids worry that no one will listen to them and believe them. I am here today to listen to you. I believe kids when they tell me about their worries.” |

| Be curious and draw out information about the other experiences of abuse or other worries they may have. |

“Has [alleged abuser ] ever done something else that you did not like?” |

| Be direct about your worries for the child. |

“You told me about your friend before. I wondered if something like that might have happened to you?” |

| Talk about next steps. |

“It is hard to talk about private or tricky stuff to someone you do not know. Lots of kids feel like that at first. You might want to talk later. Here is my phone number. You can call me. I have also given it to your teacher and your mum. I will come back and see you in a couple of days.” |

Children under 10 years of age can use and interpret language very literally. Be careful of questions that involve an abstract understanding of the abuse. For example, do not ask a child if (alleged abuser) has hurt them. The child may only define hurt as physical pain. It is better to use the child’s words where possible, or words that describe general distress such as ‘worry’ or ‘upset’.

Note

Just because information gathered from a child is not considered by the QPS to meet the threshold for criminal charges, it does not mean that a child is not at risk of harm. Information gathering and analysis must take place by practitioners to ascertain if a child’s physical and emotional needs are being met by carers.

Responding to a child's detailed disclosure

A child’s disclosure does not automatically mean that they are safe. Children who have told others about their abuse can be at greater risk of retribution from the suspected abuser or from their parents, family or community. Talk to people who are connected to the child to plan for this.

|

Practice considerations |

Conversation ideas |

|---|---|

|

Be aware of your non-verbal cues and make sure that your behaviour reflects your interest in the child and your desire to keep them safe. Thank the child for telling you about the abuse. Let them know that you believe them and that what they have told you is important. |

“Thank you for telling me about [the abuse]. It is not okay that it happened. I believe you and I will be working out how to make sure it doesn’t happen again.” |

|

Talk about next steps:

|

“My job is to keep you safe. I need to talk to some people so that we can work together to make you safe from [alleged abuser].”

“Now that you have told me about [the abuse] what do you hope will happen? What are your worries?" |

|

Talk to the child, parent and safe people about the increased risk that the child may be manipulated, intimidated or threatened by the alleged abuser or others who want to keep the abuse hidden. |

“Did [alleged abuser] say something would happen if you told anyone about him touching your private parts? What did he say?”. |

| Assess the child’s current level of safety and ask them about what they can do if they feel unsafe or at risk. Be aware that the child is also likely to have mixed loyalties, particularly where the alleged abuser is a family member. |

“You looked worried when I told you I needed to speak to your mum – can you tell me about that?” “How do you know when you are in trouble with [alleged abuser]? What does he or she do?” |

| Talk to the child about recanting to demonstrate your empathy for their circumstances and help them to feel understood. |

“It can be really tough talking about [the abuse] – sometimes kids tell people that it did not happen because it’s too hard. I want you to know that I believe you now and I will keep on believing you.” |

Practice prompt

Talk to the parent, carer and others about recanting. Predictors of recanting include being of a young age, being abused by a parent figure or someone who is in a position of power or authority over the child and a lack of support after disclosure. Scripting for this could be the following:

“Sometimes, kids might say [abuse] didn’t happen or that it wasn’t as bad. This can be really confusing, but it doesn’t mean that they lied. It often means that kids are upset about [abuse] and worried about how it will affect everyone else. Please call me if this happens and I will help you work out the next steps."

Further reading

Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse Final Report, vol. 4 (2017).

Identifying the characteristics of child sexual abuse cases associated with the child or child’s parents withdrawing the complaint (Christensen, Sharman, Powell, 2016)

Plan for safety

Investigating the safety of the child who has disclosed sexual abuse, or is showing indications that they may have been sexually abused, is the immediate role of the child protection practitioner. In addition to the individual child, the immediate safety of all children within the household must be considered when undertaking an assessment of sexual abuse allegations.

Consider:

- What needs to happen for this child to be safe at home? How long will this take?

- Who needs to know about the disclosure? How will they be told? How can we make sure the child is not the one who is telling them?

- When is the child likely to see the alleged abuser? How can this be prevented?

- What are the safety needs of all children residing within the home or having immediate contact with the alleged abuser?

- Is the safety and support network around the child able to ensure their safety?

Attention

The child should never be the person to tell their parents or the alleged abuser about their disclosure.

Further reading

Refer to the Safety planning section for comprehensive information on safety planning where child sexual abuse has occurred, is suspected, or a child is at significant risk of sexual abuse.

Published on:

Last reviewed:

-

Date:

Maintenance

-

Date:

Maintenance

-

Date:

Maintenance

-

Date:

Maintenance

-

Date:

Maintenance

-

Date:

Maintenance

-

Date:

Maintenance

-

Date:

Maintenance

-

Date:

Content updated

-

Date:

Maintenance

-

Date:

Page created

-

Date:

Page created