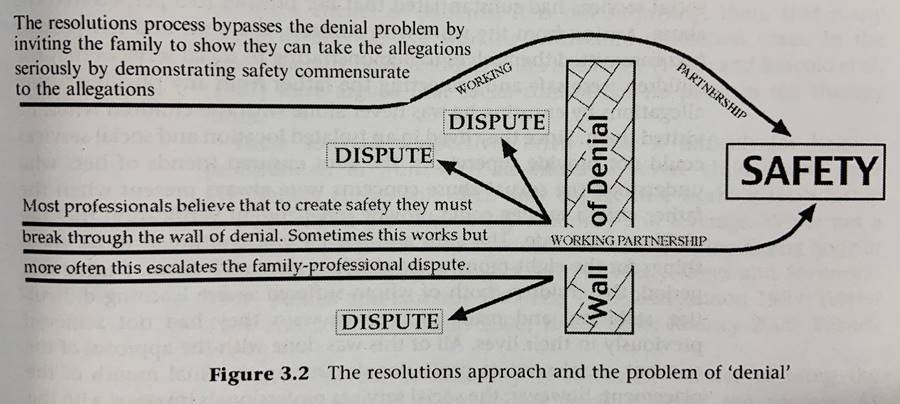

Denial of past child sexual abuse or future risk of sexual abuse by a parent or alleged abuser may present a challenge for practitioners when determining the most appropriate intervention to keep a child safe. When practice is organised around past denial rather than future safety, professionals and family members can spend a disproportionate amount of time disputing what has occurred.

Denial of child sexual abuse can cause practitioners to feel paralysed. Acknowledgement of the abuse is often viewed as being the other side of the coin to denial. In other words, it can seem to professionals that the intervention cannot continue without an acknowledgement from the parents that the abuse has in fact occurred, which can jeopardise the focus on children’s future safety. This is certainly not the case. (Turnell and Essex, 2006)

Note

The Resolutions Approach taken by Turnell and Essex addresses the problem of “denial” by taking a position that the family and Child Safety can operate from different sources of truth, so long as there is agreement that the future safety of the children is a shared goal. (Turnell and Essex, 2006)

The Resolutions Approach views so called “denial” as a continuum of behaviours ranging from complete denial, through to complete acceptance and acknowledgement. For both the alleged abuser and the parent, movement along the continuum throughout Child Safety’s involvement is expected and anticipated. Through the Resolutions Approach, safety planning takes place with a focus on finding solutions to keep a child safe into the future whilst bypassing the need for complete agreement about the past.

(Page 43, Turnell and Essex, 2006).

The alleged abuser is likely to protect themselves from arrest and alienation by doing everything possible to prevent the child from disclosing the abuse, and others from believing the abuse occurred. Consider the following ideas to respond to manipulation and coercion:

- Talk to the child about how the alleged abuser lets them know that they are in trouble or have done something ‘wrong’ to help understand how the alleged abuser may try to silence the child.

- Talk to the parent about subtle techniques that the alleged abuser might use to intimidate or silence the child from talking about the abuse. Encourage the parent to notice and respond to their child’s cues.

- Talk to the parent about the strategies the alleged abuser may use to discredit the child and isolate them from the parent and community. For example, suggesting the child is dishonest, unreliable or attention-seeking.

It is possible to safety plan in cases where the alleged abuser is denying the allegations, and where the parent does not believe fully, or is unsure about whether their child has been abused. Grounding the safety plan in the family’s daily life and their wish to keep the children safe alongside keeping others in the household safe helps practitioners work in partnership with the family and safety and support network while assessing risk and building safety. Explain to the family and network that the safety plan helps protect children and adults in the household.

Published on:

Last reviewed:

-

Date:

Content updated

-

Date:

Page created

-

Date:

Page created

-

Date:

Page created

-

Date:

Page created