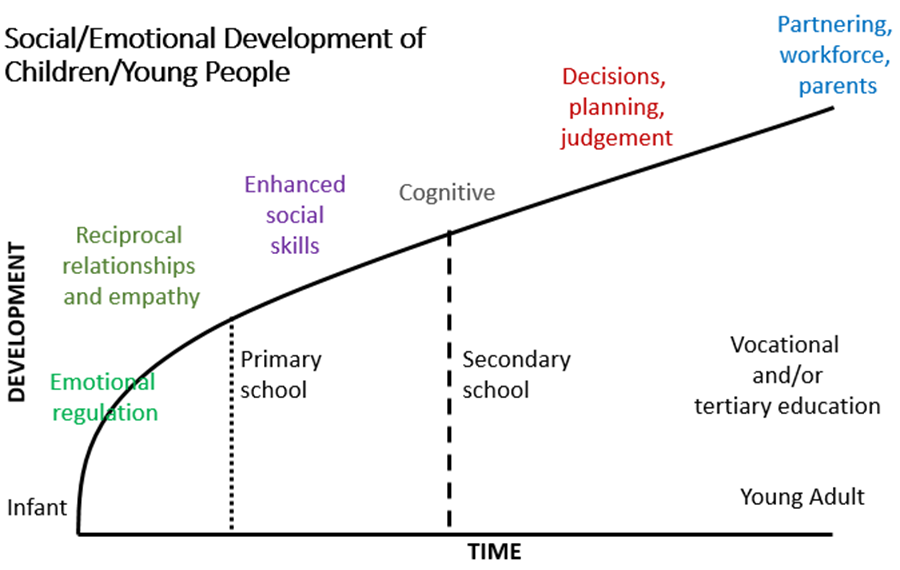

The social and emotional trajectory of children in a caring and nurturing environment is different from the trajectory for young people who have experienced harm. This highlights the needs for developmentally responsive interactions.

The following diagram shows the social/emotional development of children and young people without trauma. When trauma has been experienced, this trajectory may slow down, hit roadblocks, regress or accelerate in areas.

- In infancy:

Children have limited ability to emotionally self-regulate—defined as ‘strategies used to adjust intensity or duration of emotional state’ (Berk & Roberts, 2009 cited in the Intensive Practice Modules training material).

This skill is learnt through the caring interaction between parent and child as the child continues to develop through the trajectory. By 10, most children have a sophisticated repertoire of techniques for regulating their emotions (Kliewer et al., 1996 as cited in Intensive Practice Modules training material).

- In primary school-aged children (by about 10 years of age):

Children manage their emotions using two general strategies: problem-centred coping and emotion-centred coping. They are able to do this because they have greater cognitive ability and a wider range of social experiences on which to draw.

Children develop emotional self-efficacy, defined as a ‘feeling of being in control of emotional experiences’ (Saarni, 2000 cited in Intensive Practice Modules training material) and learn ‘emotional display rules’—that is when, where and how to express emotions.

Children learn about how to express negative emotions by interacting with parents, teachers and peers. Although the demonstration of emotion is culturally influenced, the capacity is acquired by most children. This enables them to develop empathy and the enhanced social skills needed to engage in reciprocal relationships.

- In adolescence:

Young people undergo another burst of brain development, especially in cognitive and social/emotional capacities. Cared-for young people acquire what is known as ‘executive functioning abilities’, including higher-order decision making, planning and judgement.

Young people also focus strongly on peer relations, especially on friendships, peer acceptance, dating, peer pressure and conformity. This sets them up for later developmental milestones of partnering, participation in the workforce and becoming parents.

Trauma and young people with high risk behaviours

All young people experience dramatic and rapid biological, social, emotional and cognitive changes.

The term ‘high-risk young people’ has changed over time, and language has adapted to this change. The term ‘young people with high risk behaviours’ is both a reference to the level of risk or the likelihood of danger that their behaviours are leading to, and also a reference to the trauma and cumulative harms these young people have already experienced (Department of Human Services, Victoria, 2018).

This group of young people have characteristics such as:

- they are clients within the child protection system

- generally aged between twelve and seventeen years, but occasionally as young as ten years of age

- having multiple and complex behavioural and emotional difficulties and

- requiring long term and substantial support (Department of Health and Human Services, Victoria, 2018)

For some young people, some aspects of their development may have been accelerated, for example, sexual development, because of harm experienced through sexual abuse. Other aspects may be delayed or not developed at all, for example, their emotional regulation or attachment capacity, because of neglect or abuse.

For a lot of the young people we work with, brain development has been affected, and even when resting, their brain is overflowing with cortisol (which is usually released in times of stress). Their brains are sometimes smaller and are less able to adapt to their tough environment. Being ‘street smart’ is not actually a protective factor—it is the only thing they know.

Young people with high-risk behaviours have unique developmental challenges relating to histories of abuse, neglect and complex trauma. Practitioners and safety and support network members need to create a personalised response that supports each young person’s development.

When creating safety for young people, remember their chronological age (for example, 16 years old) and their presenting behaviour (for example, acting tough, aggressive and street smart) is not a reflection of their emotional and social age, which may be closer to that of a 12-year old.

Further reading

For more information on risk factors associated with a young person’s presenting behaviour, refer to the practice guide Assessing harm and risk of harm.

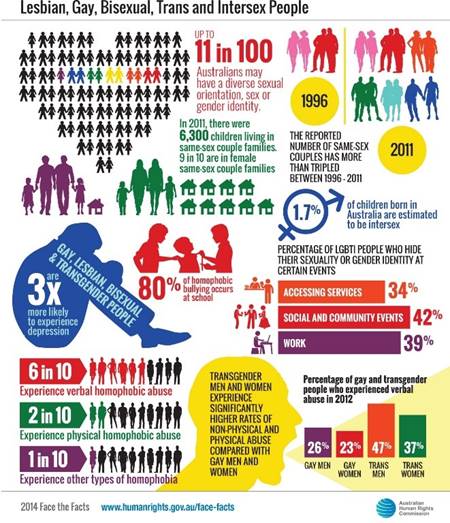

A person’s sexual orientation and gender identity is theirs, and the way they want to describe or express it and who they share that with is completely up to them. Take care to not force a young person to share information with us that they are not comfortable sharing.

The term LGBTIQA+ is broken down as:

- L—lesbian (a female who is attracted to females)

- G—gay (someone who is attracted to people of the same gender)

- B—bisexual (someone who is attracted to people of more than one gender)

- T—transgender or trans people (someone whose personal and gender identity is different from the one they were assigned at birth)

- I—intersex (someone who is born with reproductive or sexual anatomy that falls outside the typical definitions of male and female)

- Q—queer (this term has many different meanings, but it has been reclaimed by many as a proud term to describe sexuality or gender that is anything other than cisgender (a person whose sense of gender corresponds with their birth sex) and/or heterosexual)

- A—asexual (someone who has low or no sexual attraction to any gender, but may have a romantic attraction towards another person)

- +—(this acknowledges there are many other diverse sexual orientations and gender identities).

Gender identity

For some people, how they define their gender does not necessarily correlate with the physical features they are born with or their sex assigned at birth (Headspace, 2018). It is widely acknowledged that there are a diverse range of gender identities that go beyond the traditional divisions of male and female (Headspace, 2018).

While young people who are gender diverse often live exciting and fulfilling lives, a lack of understanding or acceptance of difference can lead to discrimination which compounds the trauma experience they may have experienced prior to, and while in care (Headspace, 2018).

The wellbeing and vulnerability experienced by young people who are gender diverse can be impacted on by:

- transphobic bullying

- feelings of difference

- pressure to name or deny who they are

- feeling unsupported or worried

- being rejected or isolated

- feeling stressed and pressured to conform with the sex assigned at birth.

Further reading

For further information about gender identity, please go to the 'What is gender identity?' resource developed by Headspace. For additional definitions, refer to the Glossary of common terms fact sheet from Child Family Community Australia (Australian Institute of Family Studies).

Experiencing these pressures can be stressful, especially with additional stresses they may face as a young person in care. Challenges within their care arrangement, with family contact, if they are reunifying with their family, with school or jobs and relationship building all impact on how they make sense of who they are and how they fit in the world around them.

Cooper and Dunphy (2019) outline presenting behaviours and experiences that can be indicative of an emerging gender diverse child:

| Stage | Therapeutic task |

|---|---|

| Awareness: often great distress |

Normalise the experience |

| Seeking information/reaching out for support | Encourage links and support seeking |

| Disclosure to significant others | Support integration into family system |

| Exokiratuib: identity and self-labelling |

Support articulation and comfort with identity |

| Exploration: Transition issues/possible body modification | Resolution of decisions and advocacy towawrds manifestation |

| Integration: acceptance and post-transition issues | Support adaptation to transition-related issues |

| Often occurs in childhood | Often occurs at the onset of puberty |

|---|---|

|

|

| Subtle yet visible signs a young person is experiencing gender dysphoria in themselves and in their family and school environment | |

|---|---|

|

Definitions

Sex: A person’s sex includes genetic, hormonal and physical characteristics.

Gender identity: Gender identity is distinct from sexual orientation and gender is different from physical sex. It is a very personal sense of who we are, and how we see ourselves.

Gender diversity: This is an umbrella term that includes all the different ways gender can be experienced and perceived. It can include people questioning their gender, those who identify as trans/transgender, queer, non-binary, and many more.

Transgender: This is another umbrella term covering a range of identities that cross socially defined gender norms. It may mean someone who mentally and emotionally identifies as a different gender to the one they have been assigned by society, often living their lives as that gender, and who may or may not choose to undergo any form of medical transition (for example, hormones or surgery). Or it could be a person whose gender is outside of, or between, the binary gender system altogether.

Non-binary: A non-binary person’s gender sits outside of the man or woman binary. They may identify as neither, both, or something else entirely.

Transman: This is a transgender person who was assigned female at birth, but who is a man (uses he/him pronouns).

Transwoman: This is a transgender person who was assigned male at birth, but who is a woman (uses she/her pronouns).

Brotherboy: This is a term used for/by some Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people who were assigned female at birth but who are a boy/man in spirit.

Sistergirl: This is a term used for/by some Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people who were assigned male at birth but who are a girl/woman in spirit.

Sexuality: This is who a person is attracted to, who they have/don’t have sex with, and who they wish to be in a relationship with.

Gender expression: This term covers how a person presents their femininity and/or masculinity using socially recognised markers, for example, clothes, make-up, jewellery and hair.

Cis (cisgender): This is a term for a person whose gender identity is aligned with that which they were assigned at birth.

Cissexism: This is a belief or attitude that being cisgender is more natural, healthy or superior to transgender or non-binary ways of being. (Cooper and Dunphy, 2019)

Published on:

Last reviewed:

-

Date:

Terminology change - placement to care arrangement

-

Date:

Maintenance.

-

Date:

Page created