The practitioner’s cultural competence can have a significant influence on positive outcomes for our Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people who are making the transition to adulthood.

Ensuring that this important transition is done well for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children in care is an essential part of early intervention to break the cycle of inter-generational trauma and child abuse.

The experiences of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people may differ from non-Indigenous young people, and they will have variable experiences of racism and dislocation from culture, kin, community and country. (Refer to Working with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families in the Safe care and connection practice kit.)

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people who are removed from family can be cut off from kin, culture and spirituality and are at great risk of psychological, health, developmental and educational disadvantage. They often suffer as children and later as adults experiencing grief, loneliness and a lack of belonging.

Understanding adolescence from a cultural perspective

For Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, traditional perspectives see adolescence as a time when young people go through the processes of becoming an adult and establish their place within the community. If a family is connected to their culture, and are aware of traditional practices, it would be helpful to consider these perspectives. For young people who aren’t connected to culture, it may be helpful to develop their understanding of these practices as part of their cultural support plan. (Refer to Cultural support plans in the Safe care and connection practice kit.) There has usually been a process of initiation where they are given sacred and secret cultural knowledge. In some communities, these practices continue or have been revived. Be aware of initiation traditions and encourage the young person’s knowledge and experience of traditional practices through community activities to ensure their connection to culture and identity.

This knowledge is often particular to a person's gender and eventual status/role in the community. It is a time when they learn who they are in relation to family, nation (a collection of clans), ancestors and land. (Refer to Women's business and men's business in the Safe care and connection practice kit.)

For an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young person, adolescence is the time when understanding their cultural identity is critical to their development.

Aboriginal men have a specific role in the process of a boy’s transition to manhood, and this is a very significant time for all. This is a time for learning and celebration, with song and dance forming part of the celebration.

Women’s major responsibilities in child rearing have been to teach young girls important cultural information about being a woman, including about spiritual and social wellbeing, ancestral laws, information on how to care for land and information on fertility and child rearing. Mothers, grandmothers and aunties also have responsibilities for teaching male babies and young boys respect for women as well as basic hunting techniques.

Today’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander grandparents have critical roles in imparting culture, particularly through storytelling and assisting parents in the raising of their children.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people: shared cultural grief

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people may share the experience of cultural grief as a result of personal experience, shared experiences or intergenerational trauma. (Refer to Intergenerational trauma in the Safe care and connection practice kit.)

Young people’s reactions to trauma (cultural grief) can often be misunderstood as ‘difficult’ or naughty’ behaviour. This cultural grief can manifest itself in the following ways:

- reliving the trauma through repetitive play, frightening dreams, or distress when reminded of the event

- having negative thoughts and moods such as fear, guilt, sadness, shame, or confusion; losing interest in activities that used to be enjoyed; and spending more time alone.

- feeling wound up—having trouble sleeping or concentrating, feeling angry or irritable (or having temper tantrums), being easily startled or constantly on the look-out for danger, or doing things that might be risky or dangerous (especially older children and adolescents)

- displaying general misbehaviour or attention-seeking behaviour

- performing poorly at school

- having unexplained aches and pains

- demonstrating substance use

- acting out or displaying general anti-social behaviours.

Additionally, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people are likely to experience amplified feelings of shame, despair, demoralisation and hopelessness—or what is sometimes called ‘community depression’, which is a shared cultural grief born from intergenerational trauma and oppression.

Note

With several generations of Indigenous people being denied normal childhood development, the opportunity to bond with parents and experience consistent love and acceptance, both the skills and the confidence to parent have been damaged, with Indigenous children over-represented in the child welfare system. (Atkinson, S. and Swain, S., 1999, cited in SNAIC, 2008, p. 4).

The child placement principle

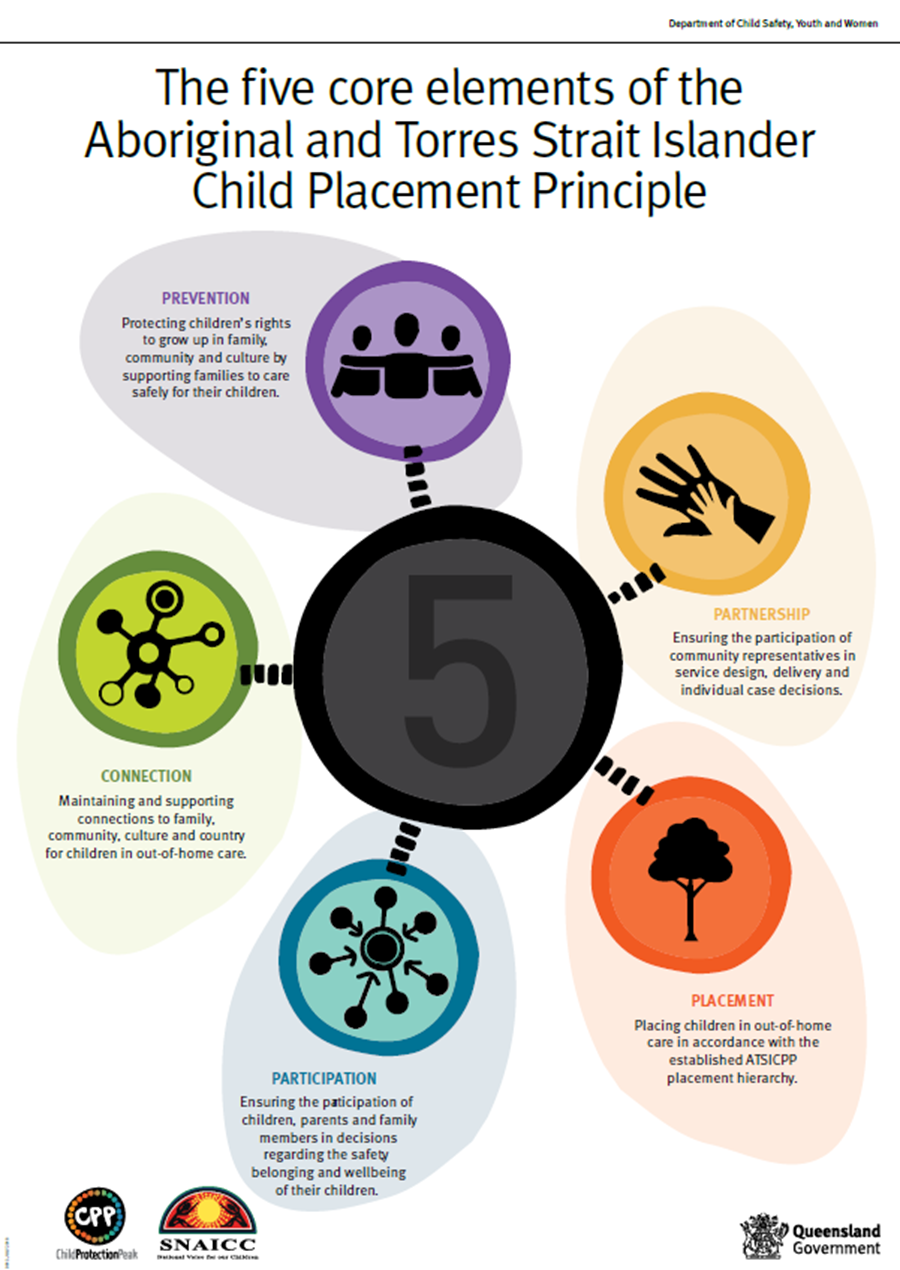

The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Child Placement Principle (the principle) is a legislative responsibility outlined in the Child Protection Act 1999 (the Act). The five elements of the principle - prevention, partnership, connection, placement and participation - guide care arrangement decisions and actions taken for Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander children.

The principle is based on an identified need to advocate strongly for the best interests of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children and is now integrated into legislation and policy across Australia (Arney et al., 2015). Inclusion of the principle into decision-making processes aims to enrich and preserve the connection Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children have to their family and community as well as enhance their sense of identity and culture (Arney et al 2015).

Published on:

Last reviewed:

-

Date:

Maintenance

-

Date:

Maintenance

-

Date:

Maintenance

-

Date:

Page created