When a decision is made that there will be ongoing intervention for a child in need of protection, a case plan is developed to address the child’s care and protection needs. Concurrent planning is the type of case planning undertaken when a child is in care and where more than one option for permanency is pursued in order to achieve a timely, stable long-term care arrangement.

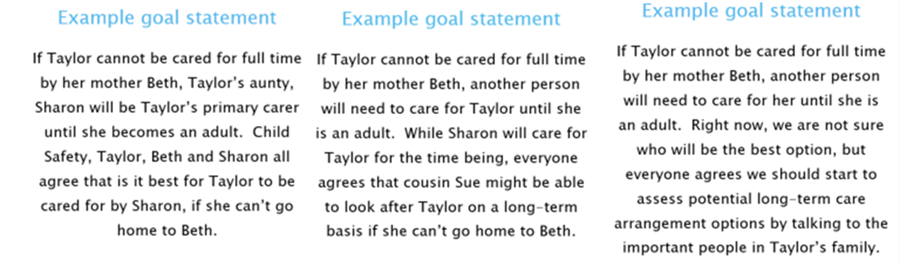

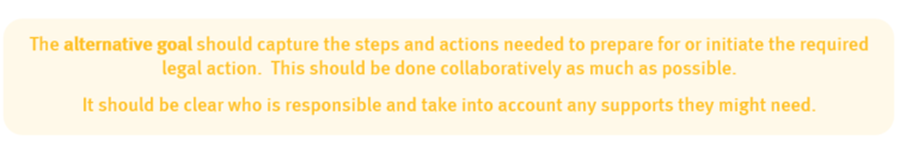

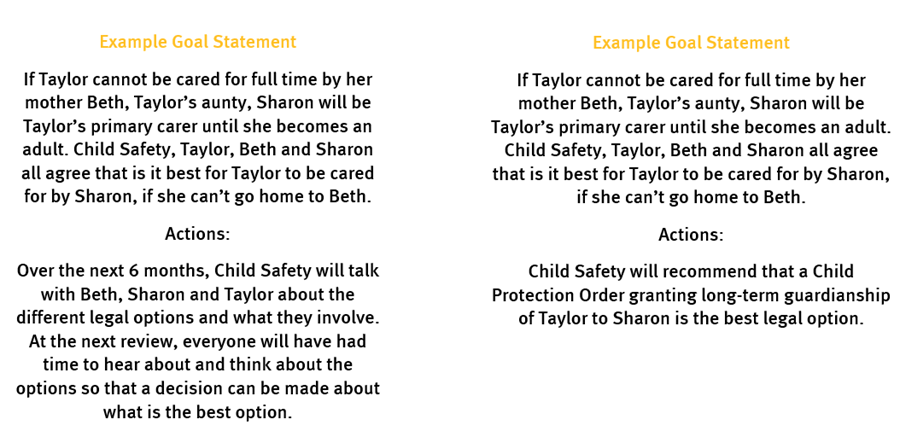

The Child Protection Act 1999, section 51B (2) specifies that the goal for best achieving permanency, and actions required to achieve that goal, must be included in the child’s case plan. If the goal for best achieving permanency is to return the child to the care of their parent, the case plan must also identify an alternative goal, in the event timely reunification is not possible. Identifying and planning for both primary and alternative permanency goals at the same time rather than sequentially, is central to concurrent planning.

If the child is subject to a long-term guardianship order for two years, a case plan review will be undertaken to determine whether the order continues to be the best option for achieving permanency for a child. The alternative goal will also be reviewed as part of this process.

The Child Welfare Information Gateway (n.d) describes concurrent planning as

“…identifying and working toward a child's primary permanency goal (such as reunification with the birth family) while simultaneously identifying and working on a secondary goal (such as guardianship with a relative). This practice can shorten the time to achieve permanency if efforts toward the primary goal prove unsuccessful because progress has already been made toward the secondary goal”.

The aim of concurrent planning is to expedite permanency for a child and requires actions to be developed and progressed simultaneously for both the primary and alternative permanency goals from the time a child comes into care, until a permanency decision is made. A useful way to describe this to families is that the concurrent plan is a ‘just in case plan’ - if reunification is unable to be achieved, the child needs to have a ‘just in case’ plan ready, that has been thought about and supported.

In some jurisdictions, concurrent planning is known as parallel planning, but this term does not accurately reflect what happens in practice. Parallel planning implies two plans, running side by side. In practice, planning around primary and alternative permanency goals involves many crossovers or intersections, with the progress of one informing and influencing the other.

Concurrent planning is…

Note

Concurrent planning starts from the first day a child enters care and continues until reunification and case closure, or when an alternative permanent arrangement is achieved.

Further reading

Early and collaborative concurrent planning

Sometimes concurrent planning in the permanency context might feel like Child Safety are expecting parents will not be able to care for their children. Or it could be seen as something that undermines the goal of reunification (Tilbury and Osmond, 2006). Practitioners may be concerned that discussing concurrent planning with families from day one will damage the relationship. It is important that early messaging around concurrent planning is not discouraging or presented as a ‘bad news’ option. Instead, introduce concurrent planning by outlining the benefits:

- it can achieve timely resolution to support sustainable permanency for the child

- there will be fewer placements for the child if reunification is not viable

- family members are involved to identify potential placement options

- communication with the family about plans and actions to support primary and alternative permanency goals is open and transparent from day one.

(Child Welfare Information Gateway, 2018).

Early and collaborative concurrent planning with families means that the family and Child Safety can draw on existing resources and strengths in the family, develop enduring relationships to safeguard the child’s connections into the future and work transparently together to co-design solutions and plans that are more likely to succeed in the long-term.

When practitioners keep concurrent planning in focus as an essential part of case planning, conversations about primary and alternative permanency goals become an integrated and expected part of the process. Parents respond well to transparency, and being upfront and honest about the benefits of concurrent planning can decrease conflict and aggressive behaviours sometimes experienced when parents feel they are not in control or not being heard.

Further reading

Refer to Working with parents.

Remember that parents and family members want the best outcomes for their children. Focus on this shared goal when case planning for permanency and consider multiple ways to achieve this. When a parent makes a suggestion, consider the option fully and ensure they feel heard and empowered to be part of the process.

Lack of early, effective and collaborative concurrent planning can have lasting negative effects for children and families. Children can ‘drift’ in care without experiencing a stable and predictable care arrangement. Parents are more likely to describe feelings of confusion, hopelessness, lack of motivation, frustration and a sense of ‘changing the goal posts’.

Concurrent planning across the dimensions of permanency

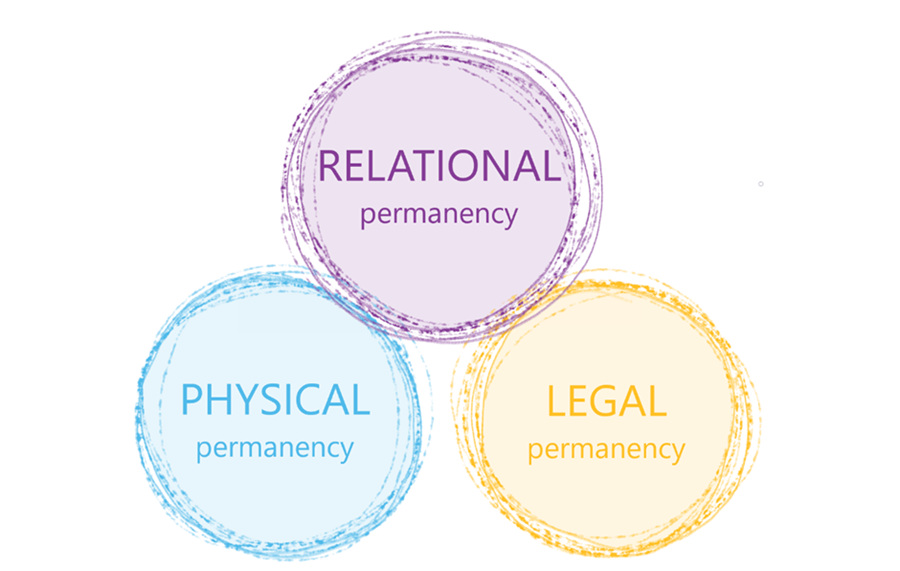

When undertaking concurrent planning, consider the three dimensions of permanency - relational, physical and legal - for both the primary and alternative permanency goals.

Tip

Relational and physical permanency for a child is directly linked to positive and lifelong outcomes. Legal permancy decisions support the relational and physical permanency areas for a child.

Appreciation of these dimensions highlights that permanency planning is much more than placement (Tilbury and Osmond, 2006). It recognises that children need consistent, predictable and loving relationships, a sense of connectedness and belonging to families and communities - particularly for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children - and a stable place to call home (Tilbury and Osmond, 2006).

A lack of recognition of the multidimensional nature of permanency can lead to children feeling a sense of impermanence (Stott and Gustavsson, 2010). Each dimension influences and overlaps with the other, and permanency cannot be progressed if these interdependencies are not acknowledged. For example, focusing on legal permanence without securing relational and physical permanence will not support long-term stability. It is necessary for all three dimensions of permanency to be actively considered during concurrent planning.

When exploring permanency options for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children, the right to self-determination must be acknowledged. Active efforts that are purposeful, thorough and timely are key to enabling their safety and wellbeing (SNAICC, 2018) and are essential to promoting permanency by ensuring that the safe care and connection of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children with family, community, culture and country is central to planning.

Attention

Refer to the practice kit Safe care and connection for further information about active efforts.

Relational permanency

Note

‘The single most identified factor contributing to positive outcomes for children involves meaningful connections and lifelong relationships with family.’ (Campbell, 2018).

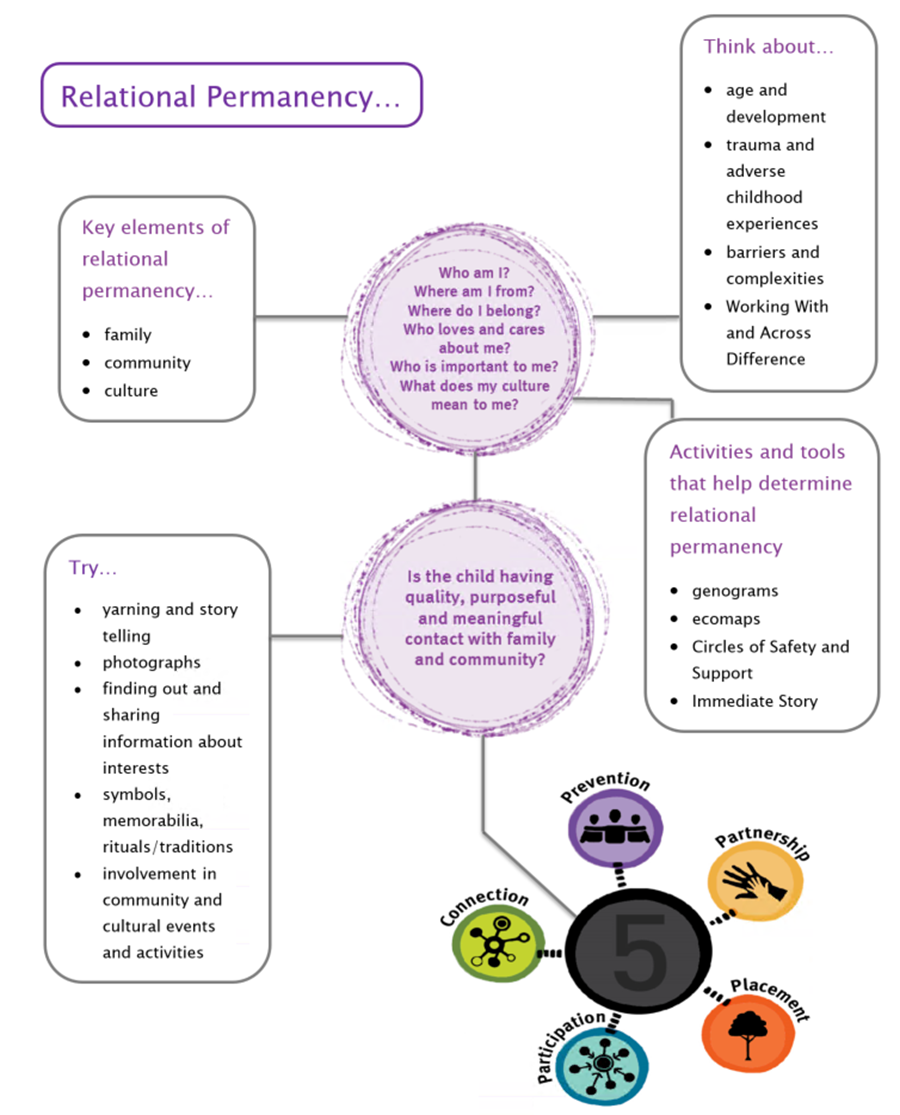

Relational permanency can be explored through key questions about the child’s sense of self and their world. Consider the questions in the the diagram below (in an age and developmentally appropriate way) to help conversations with the child and hear their views about who they think loves and cares for them, and where they feel they belong. These views are important to decision making when developing a concurrent plan.

Further reading

Refer to Working with children.

The child will form and maintain relational connections by spending time and sharing experiences with the people who care about them, the people who are important to them and by going to places of significance to them.

Practitioners must be mindful of the right of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children to grow up with a sense of belonging and identity, to know where they are from and how they fit into and can connect with their family, mob, community, culture and country (SNAICC, 2018). For Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children in care, yarning is an important part of building relationships. Hearing stories about family members, ancestors and cultural traditions helps to build their cultural connection and belonging and supports developing relational permanence.

Note

The child’s family must decide who is important to the child. Defining kin is the responsibility of the family or others who hold cultural authority for the child. This is not a decision for Child Safety.

Children in care are less likely to have strong and enduring relationships. At times, the child’s safety and support network need to consider how to strengthen this area. Review the child’s Circles of Safety and Support Tool to understand who is already around the child and who is missing. Ask family and other network members who will also be able to help. Meaningful plans for the child to connect and spend time with significant people in their lives is essential to their relational permanency and will influence and intersect with permanency in other areas.

As well as making connections, also think about supporting a child when relationships end. Be open and talk about when people may be in their lives for a short time, while others are around for much longer. Help to build understanding, expectations and plans around transitions and endings, and help the child keep close the memories of people who have been part of their lives, who they may not spend time with anymore.

Further reading

For more information about family connection through safe, quality and purposeful contact for a child in a care arrangement, refer Practice Guide Family contact for children in care.

Physical permanency

Note

Physical permanence is more than a physical location – it includes the stability of norms, rules, expectations, values and traditions (Stott and Gustavsson, 2010).

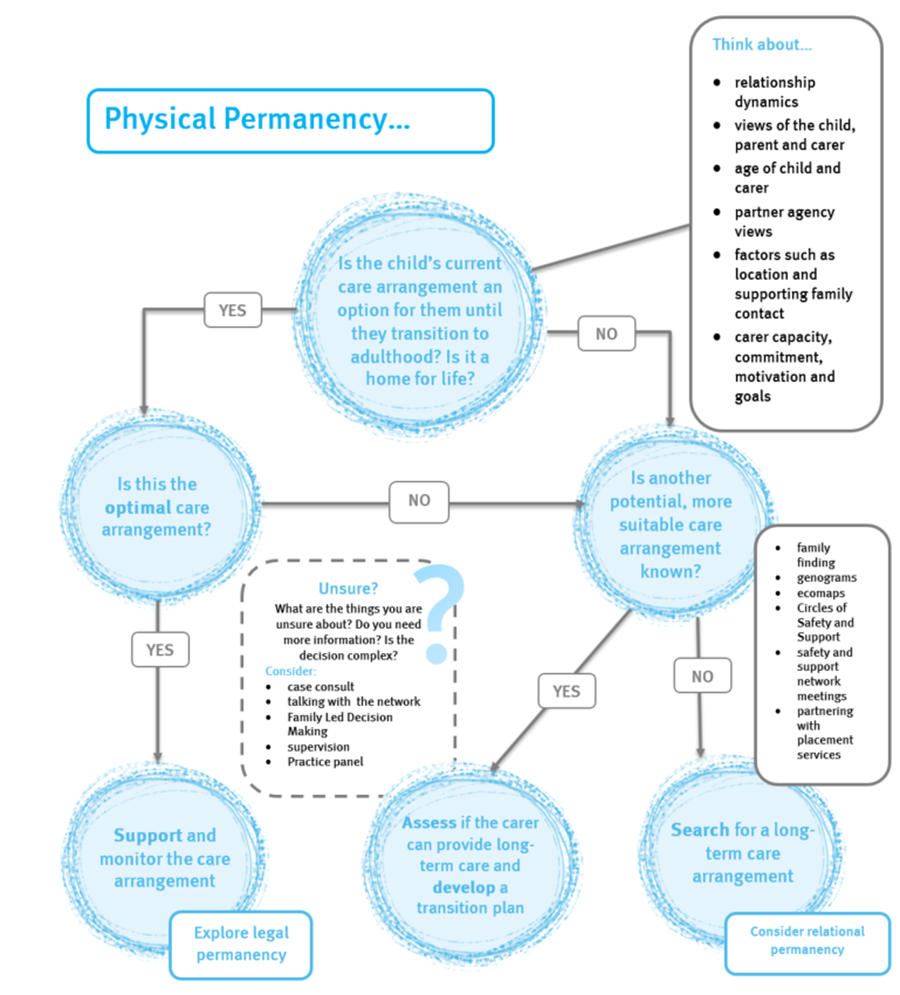

Sometimes a care arrangement meets a child’s immediate daily care needs, but not their physical permanency needs. Consider other potential care arrangements by looking at the child’s network and taking into account relational permanency. Are there people in the child’s life who they are already connected to that could also have a role in supporting their physical care and wellbeing in the future? Can the child’s parents and network identify a family member willing to be assessed as a long-term or permanent kinship carer and guardian? There may also be full time or shared care arrangements options which can be explored further. For example, can a carer that looks after the child for short breaks be considered as a permanent carer? Or could two short break carers provide shared care for a child to manage their primary care needs across the two households?

Tip

Strengths based case work encourages the parents and network to identify potential alternative care arrangements.

When looking at connections, it may be that, at first, we know little more than a name. By exploring, developing or re-establishing relational permanency, a relative or someone in the network who has lost contact with the child and family may be identified who could support physical permanency.

Practice prompt

When planning to secure physical permanency, consider also the most suitable order type (legal permanency) to ensure these needs are met.

Continue working with the network to find the ‘just-in-case’ plan. Concurrent planning allows the child to remain in their current short-term placement while a permanent care arrangement is identified and assessed. Be mindful that there might need to be more than one ‘just-in case’ plan, which enables additional alternative care arrangements to be considered in the event family members are not approved, or a situation changes and identified options are no longer viable.

Tip

Consider whether there are things that can be done to strengthen the current care arrangement so it could be considered as a suitable alternative permanency goal. Is more information needed to feel more confident about the care arrangement as a long-term option? Supervision, case consultations or complex case clinics are all ways to help explore these decisions.

The diagram below provides an example of a pathway to achieve physical permanency. Remember that phyiscal permanency is not just about the care arrangement. Other considerations such as connections to school, sport, health care and community engagement also need to be considered and become especially important if a planned care arrangement breaks down.

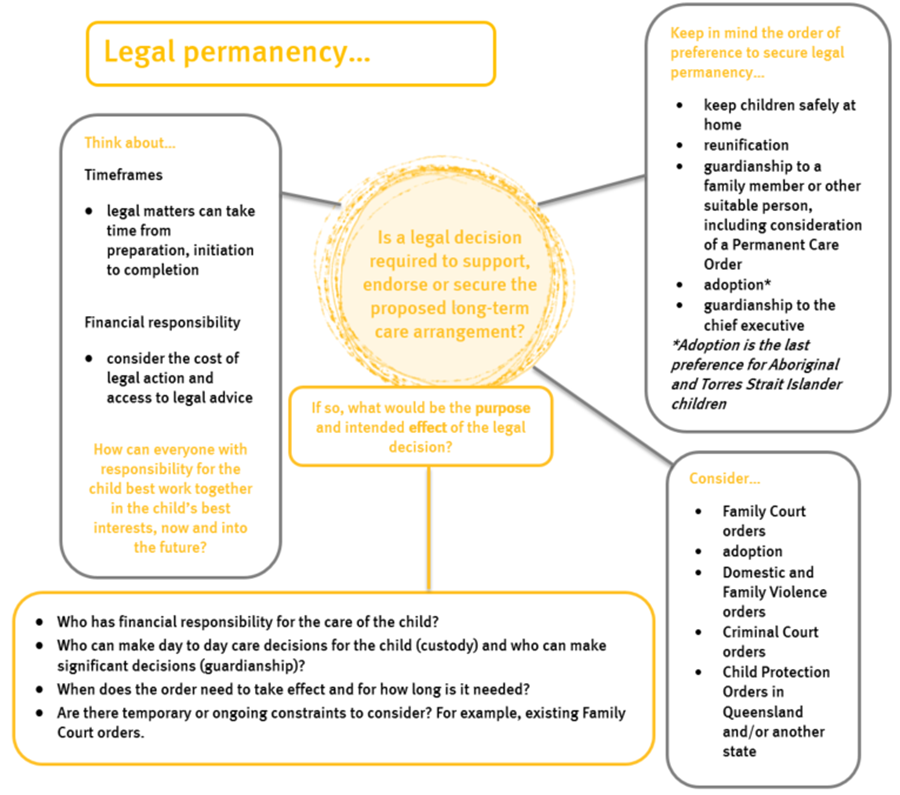

Legal Permanency

Note

Focusing on legal permanency without considering relational and physical permanency, can result in practitioners securing a ‘place to stay’, rather than a ‘home for life’ (Osmond and Tilbury, 2012).

Different dimensions, different timelines

During case planning, there may be circumstances when permanency is not initially progressed across all three dimensions. A robust concurrent plan can assist decision making by having clear alternative options outlined for each dimension of permanency, just in case.

For example, legal permanency may be delayed if the permanency goal was for a permanent care order to be granted to an extended family member, however the Childrens Court requests further documentation prior to making a decision. In this situation, it is important to focus on maintaining relational permanency while legal permanency continues to be pursued. By ensuring connections in the child’s life are stable, their safety and support network can build safety and work collaboratively to secure the permanency goal.

Another example of when not all permanency dimensions are progressed in the first instance is when a young person is living in a place that is not approved and is frequently reported missing. While parts of physical permanency are not being achieved, aim to stabilise where possible. Can the young person continue to attend the same school and see the same medical professionals? Ensure relational permanency and connections to their safety and support network to assist in supporting the young person through this period.

Practice prompt

If a child has strong relational permanency, they have a tendency to become more resilient and respond better to challenges in other permanency areas.

Informing primary and alternative permanency goals

When working with parents to concurrently plan for permanency, consider the individual family and their strengths and needs. Start with gathering information to inform your conversation with children, their families and networks:

- Information about worries, that is, why the child entered care. Read the Investigation and Assessment outcome, understand the worries that led to the child being placed in care.

- Information about family strengths and resources. Look at the Collaborative Assessment and Planning Framework tool, read minutes from previous practice panels, and information from investigation and assessments. Ask the family. Have continuous and clear conversations with the family to allow for planned goals and outcomes to be monitored, celebrated or revised.

- Information about the child’s age, development and needs. Read the child strengths and needs assessment. The characteristics and needs of the child will influence the permanency options that can be considered.

- Information about perspectives of other professionals and carers. Consider the views provided by other professionals or support network members working with the family.

- Consider the parental strengths and needs assessment which can give you information quickly about the strengths and challenge areas for a parent.

Attention

Working towards timely permanency for a child is part of all interactions between a CSO and a parent, child or network member. Concurrent planning is an ongoing and fluid part of case work and is documented clearly in a child’s case plan.

Concurrent planning when reunification is not possible

If reunification cannot be achieved, this does not mean that the alternative permanency goal identified through concurrent planning excludes or restricts the parents from the child’s daily care and upbringing. The alternative goal can focus on a having safe and stable care arrangement that supports maximum involvement of the child’s parents and family in their lives now and into the future to the extent that it is safe.

When a child is on a child protection order, it is rare that there is no parent or family involvement. Usually, there is at least one parent or family member who is willing to be a part of the child’s life in some way.

One way of thinking about this when developing a concurrent plan is to consider a scale where at one end, the parent and family are doing everything to care for and protect the child without Child Safety involvement, and the other end is that they are not involved at all.

Where is the situation currently? Consider and define the permanency outcome. For reunification, this will generally be for the child to return to the parent/s with no Child Safety involvement.

If reunification is not possible, an ideal concurrent plan will work to maximise the involvement of the child’s parents and family connection, while keeping the child safe. For some children, this means they are cared for all of the time by family. For others, it will mean they are looked after by an approved carer all the time or may have a new guardian appointed. For many, when working towards achieving permanency, it will mean something in between.

But….sharing care isn’t easy – it takes relationships, communication, patience, love, focus and hard work. A good question to ask is ’is everyone focusing on the child and their needs?’

And….it isn’t just about who has the primary carer role. There are many ways that we can build, promote and maintain the parent and family’s involvement. This is vital when working towards reunification.

Further reading

Published on:

Last reviewed:

-

Date:

Maintenance

-

Date:

Content updated for SDM changes.

-

Date:

Maintenance

-

Date:

Maintenance

-

Date:

Maintenance

-

Date:

Maintenance

-

Date:

Maintenance.

-

Date:

Page created