Recruitment

Foster and kinship carers are a key component of the child protection system, with Child Safety, carers and care agencies working in partnership to meet the significant needs of children and young people in care. Regular recruitment strategies and the provision of responsive support and training leads to the best outcomes, that is, the retention of carers and increased security and stability for the children in their care.

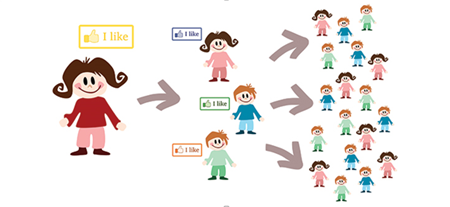

Successful carer recruitment and retention can create a cycle where satisfied carers generate interest in others through ‘word of mouth’. Word of mouth has been identified as the most effective strategy for recruitment, through a person either knowing or meeting other carers (Thomson et al, 2017). Including current carers in recruitment campaigns is also important.

Additionally, recruitment strategies that focus on recruiting carers for a specific child in need of care, particularly a child known to the potential carer, are likely to be more effective (Osborn et al, 2007).

In all Australian states the gap is growing between the numbers of children needing care, and the number of qualified carers.

In Queensland, there is a critical need for more foster and kinship carers. Child Safety data provides a picture of this critical need. As at 30 June 2019:

- 10,248 children were living away from home with 84.9 per cent (8,696) in home-based care, 9.3 per cent placed in a residential care service and 5.9 per cent were in other locations (including hospitals, Queensland youth detention centres, independent living). Since 30 June 2015, the number of children in care has increased by 14.6 per cent.

- There were 5,345 carer families, made up of 3,522 foster carers, 1,610 kinship carers and 213 provisionally approved carers. Overall, the number of carer families has increased by 6.6 per cent since 30 June 2015 (5,012).

In the 12 months from July 2018 - 30 June 2019:

- 1525 new carer families commenced in the role

- 1394 families ‘exited’ the role, meaning their carer approval ended, and no new approval for their care provision was made over the following 60 days. (Dept. Child Safety, Youth and Women, Our Performance (2020)

There are several influences linked to carer retention considerations including:

- the level of satisfaction a carer experiences in the role

- their family circumstances

- the extent they receive financial help, training and support, including support from other carers (cited in Thomson et al, 2017).

The level of support provided by Child Safety is also critical, as identified through exit interviews and surveys undertaken with carers by Queensland Foster and Kinship Care. There is opportunity to strengthen partnerships and collaboration between CSOs and carers to ensure carers are a respected, valued and supported part of a child’s safety and support network and care team.

With the pressure on family-based care arrangements for both foster and kinship care increasing, reliable and responsive support from CSOs to family-based care arrangements is vital in the retention of carers and stability for children in care. By maintaining and building a larger pool of carers, Child Safety and licensed care services have the opportunity to better match children’s needs with the most suitable carers. This increased pool ensures more long-term, successful and rewarding care arrangements for children who are unable to live with their own families.

Note

We need to provide excellent support to current family-based carers, as word of mouth is the most successful recruitment strategy and carer stability is the key to care arrangement stability.

Carer support

To help carers respond to the complexities of looking after children in care, they require individualised and multi-dimensional support (Thomson, 2017; Thomson, 2016). While caring can be a fulfilling and rewarding experience, a range of stresses associated with looking after a child with multiple needs, and navigating different elements of the care system, can influence how long an individual or family stays in the role.

Further reading

Find out more about the support and retention of carers in Recruiting and Retaining Foster Carers. Research to Practice Series

Practice prompt

You can read more on how to support carers in the Responding section of this part.

Training

Training for carers, both foster and kinship, is a significant way we can provide support. Pre-service training is compulsory for all foster carer applicants.

Kinship carers are not required to attend training, however, they are encouraged to attend foster carer training to enhance their knowledge and skills. This may partly explain the research that suggests some kinship carers feel they often receive less support than carers who are not related to the child (Thomson, 2016).

Research further identifies that carers want training that is both practically oriented and nationally accredited, as this supports the professionalisation of foster care and is linked to increased payments and improved support (Osborn et al 2007).

Pre-service training is one component of the training we can provide to family-based carers. There are many training programs, workshops, conferences, online modules and non-government organisation-provided training programs family-based carers can attend to increase their knowledge and skill sets to provide care for vulnerable children.

It is the job of the practitioner, in partnership with family-based carers and carer support agencies, to identify these training opportunities and support the carers in attending.

Note

Information about Child Safety’s pre-service and in-service training packages is available through the Child Safety website.

Understanding how fostering impacts on families

Becoming involved in fostering affects every part of family life, however the impact on the biological children of carers is often unrecognised or overlooked (Noble-Carr et al, 2014; Hojer et al 2013). These children make a significant contribution to the fostering experience and face challenges and changes that must be acknowledged (Noble-Carr et al, 2014).

Key findings emerging from research conducted by Hojer et al (2013) into the impact of fostering on the children of foster carers found that:

- involvement in the initial decision to foster increases their understanding around how they themselves may be affected and influences how they will adapt

- ongoing relevant information about the fostering process as well as about the children who will be placed with their family helps them to feel involved and be prepared

- there must be caution around sharing sensitive information

- children need time alone with their parents

- children should be given space and opportunity to discuss any problems or worries

- it is necessary to prepare children of carers, where possible, that a care arrangement is going to end.

Practice prompt

See the Responding section of this part to read more strategies on how you can support and include the families of carers in sharing the decision making and in contributing to the carer household.

Further reading

Understand more about what foster carers’ own children think about being part of a care family by reading The impacts of fostering on foster carers' children.

Understanding technical problems versus adaptive challenges

There are many complex issues arising in relation to children’s care arrangements. It can be helpful to distinguish between technical problems and adaptive challenges. Being aware of the difference and how to respond can help ensure your response is the most appropriate for the situation.

In 1994, psychologist Ronald Heifetz made the distinction between technical problems and adaptive challenges we face in our work. Essentially, he said that a technical problem yields the right answer through the application of an appropriate and pre-made plan.

Many problems in mathematics, science, engineering or business feature technical problems that have right answers that ‘fit’ the problem. An example of a technical problem in a care arrangement is a carer not having authority to care for a child. The solution is to provide the carers with an Authority to care, which outlines their right to care for the child under the applicable section of the Child Protection Act 1999 (the Act).

An adaptive challenge doesn’t have a clear, pre-made particular or certain answer. Adaptive problems are real-world problems where data is uncertain, conflicting or ambiguous, where people can reasonably disagree about appropriate actions to resolve the problem or where personal ethics or values are in conflict.

| Characteristics of technical problems | Characteristics of adaptive challenges |

|---|---|

|

|

When you hold a position of authority, people inevitably expect you to treat adaptive challenges as if they were technical—to provide a remedy that will restore equilibrium with the least amount of pain and in the shortest amount of time. That puts an enormous amount of pressure to have an answer rather than raise (and sit with) the really tough questions. (Heifetz, 1994) Being rigorous in searching for solutions with carers and children, and critically reflecting on our work is key when working through adaptive challenges.

Examples of technical problems in a care arrangement include:

- How do you refer a family/child to a service?

- How do you fill out a placement agreement?

- How do you complete a case note after a home visit?

- How do you make a mandated report about suspected harm by a carer?

Examples of adaptive challenges about placements may include:

- What foster and kinship carer agency is the best match to support this family-based carer?

- Will this young person achieve better outcomes in this family-based care arrangement?

- How do I document all the nuances of what occurred during the home visit today while remaining objective and descriptive?

- Do I tell the carer I am reporting their behaviour as suspected harm to the child?

There are many technical issues within care arrangement as well as adaptive challenges. Being aware of the difference between the two helps ensure your response is the most appropriate for the situation. This will contribute to increased partnership between Child Safety and carers, leading to better outcomes for children in care.

Published on:

Last reviewed:

-

Date:

Maintenance

-

Date:

Maintenance

-

Date:

Maintenance

-

Date:

Maintenance

-

Date:

Terminology change - placement to care arrangement

-

Date:

Maintenance.

-

Date:

Maintenance.

-

Date:

Page created